On New Year’s Eve 2021, I traveled to BanPong to meet with my TBR researcher colleague Alex (aka TS) and his wife. They had located 3 individuals in the area who had personal stories to tell. I added a fourth and we stumbled onto a fifth as we explored the area.

First we traveled to the area just behind Wat Nong PlaDuk, which is located just to the south of the marshalling yards. There we found 86yo, Boakai Sriprasert at her home. She shared a series of TBR-related stories.

- While she herself had spent the war years in nearby Nakorn Pathom, her husband Nit (now deceased) had lived in the area as a teen. She showed us what is most likely the remains of an incendiary bomb dropped at part of the bombing raids on the NongPlaDuk railhead just a few dozens of meters to the north.

- She told of finding human remains: bones and articles of clothing in the post-war years as they farmed the land. These had long since been taken to the local temple for cremation; burial place unknown.

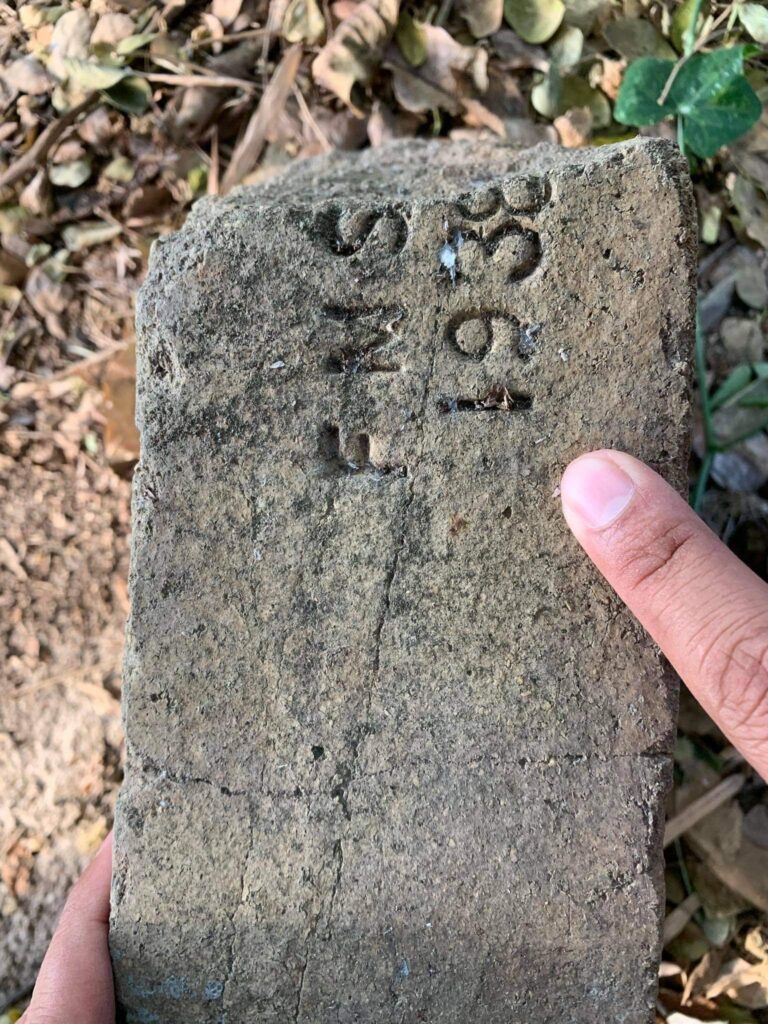

- She took us to a make-shift shrine in the back corner of her land that contained a small Japanese war-era flag. Beneath that shrine was an iron gear and a partial brick that bears the date 1938. [We convinced her to move the flag into her house to better protect it from the elements as it was showing signed of deterioration.]

- She next took us to a relative’s house where we visited a 2m square concrete structure. It had the appearance of a well or water tank, but its true purpose is unclear. The family gathered around these intruders on their land (us) and expanded the story that there had been a rail-spur and a workshop of some sort in that area. As they and their neighbors developed and farmed, they found many pieces of rough concrete (cement with large gravel) and short sections of iron rails scattered across the land. Apparently, prior to departing the Japanese destroyed whatever structures were there, leaving only scattered debris.

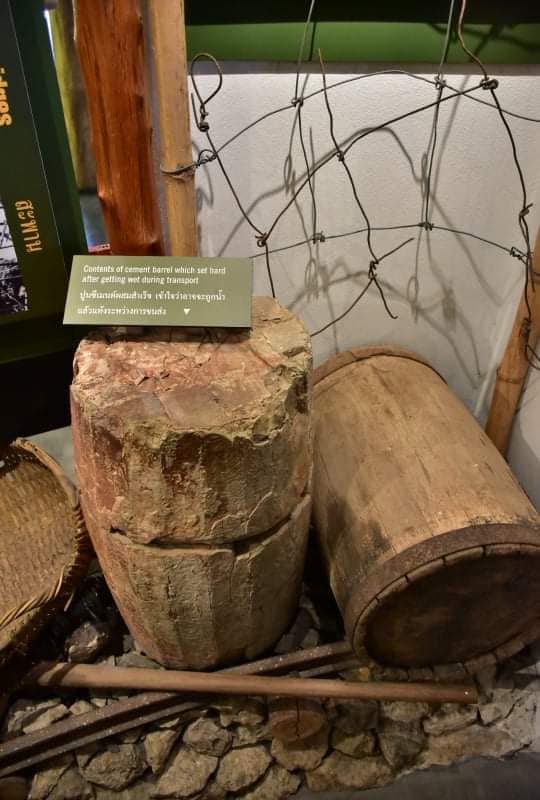

- One of the family took us to a shed where he kept a wooden barrel that they claimed was war-era as well as 2 broken bricks emblazoned with the letters M-__-T the middle portion was obscured by weathering. They claimed that many such bricks – which were also seemingly made of concrete not clay – were scattered across the land a well. [see the barrel update below]

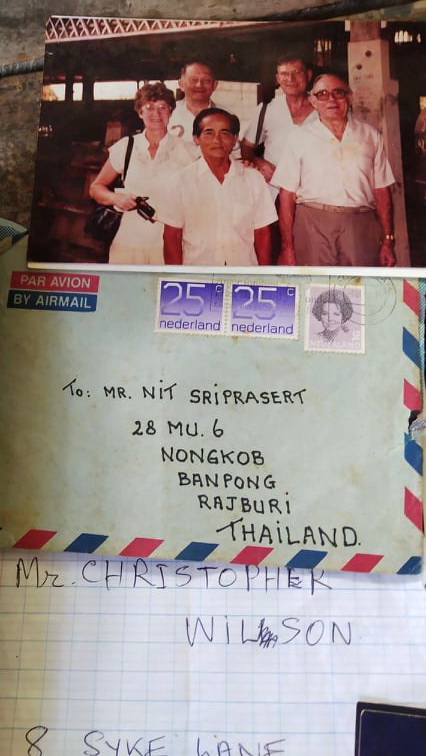

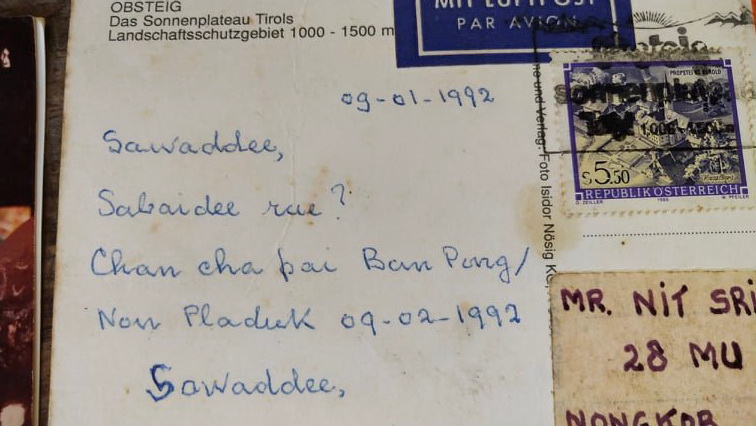

- Back at her house, she produced a packet of letter and photos as well as a notebook that her husband has collected over the years. Apparently a few of the former Dutch and British POWs (one named Christopher Wilson) had managed to keep in touch with him over the ensuing years.

- She also claimed that the school at the NongPlaDuk temple had on display a few artifacts that had been collected over the years. But since it was NYEve, no one was at the school. A future visit will be needed.

As if the world were not small enough already I just received this 2008 interview with Khun Nit courtesy of Peter Winstanley:

SIAMESE (THAI) LABOURER ON THE BURMA THAILAND RAILWAY

KHUN NID

On 29 February 2008 when near Non Pladuc, I had the opportunity and privilege of interviewing Khun Nid, who was a Siamese national employed by the Japanese in 1942. He was a very modest man, who was quite proficient in speaking English, possibly a result of working with the British POWs. He had a clear recollection of the arrival of the first POWs to work on the Burma Thailand Railway at Non Pladuc where he said workshops were built. He also recalled there being Dutch POWs, but, did not recall any Australian POWs. A possible explanation, would be that he identified Australians along with the British.

He was in charge of a work party of natives on Siam and was responsible for selecting them and received 1 Baht per day pay plus 2 meals. The Japs treated them reasonably and they worked 7 days per week with few breaks..

He recalled the bombing raids on Non Pladuc and also remembered there being bunkers there. It could be that he recalled the slit trenches which the Japanese finally allowed the POWs to dig. But, only after there had been many fatalities and injured amongst the POWs.

He remembered the Japanese guards punishing the native labourers by making them carry sand bags. He worked for the Japanese for around 3 years.

Post war he became a farmer and married a lady who came from Nakhon Pathom about 4 or 5 years after the war ended.

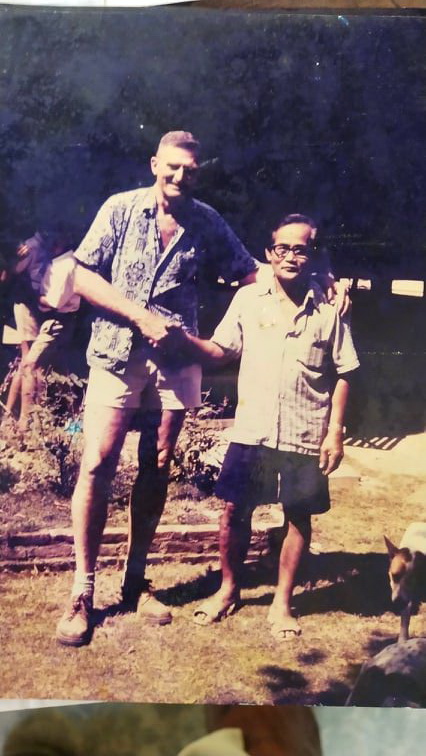

They live in a spacious home in the vicinity of Non Pladuc. Near their home are the foundations of some of the workshops which were built in 1942. His wife took us and showed us the foundations. She also showed us some items which were said to be from the infamous Burma Thailand Railway. These included a two man cross-cut saw (see picture below of Peter Winstanley and Khun Nid’s wife) and pieces of concrete (also see below) which looked as though they could have been the remains of concrete sleepers brought from Malaya. The pieces of concrete bore the marking “F.M.S.R. 1938”. Their home is in the vicinity of a POW cemetery and as a token of respect they have placed a small temple in the area.

It was a privilege to speak with Khun Nid and his wife.

Lt Col Peter Winstanley OAM RFD JP who conducted the interview and Major Beverley Poor who took photograpghs. Khun Vivatchai Wongsuvat interpreted.

It also included photos of two artifacts:

================================

Our next stop was somewhat less fruitful. A few kilometers to the west is Wat Kok Mor. A discussion with a vendor confirmed that behind the local school, there was a cemetery of some type dating back to the war-era. But on NYEve there was no one at the school either to provide more information or access. It remains on the list of places to visit.

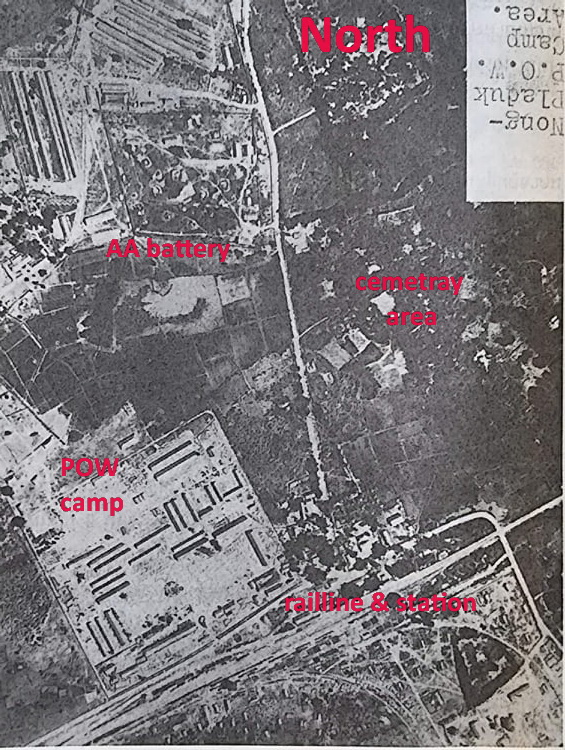

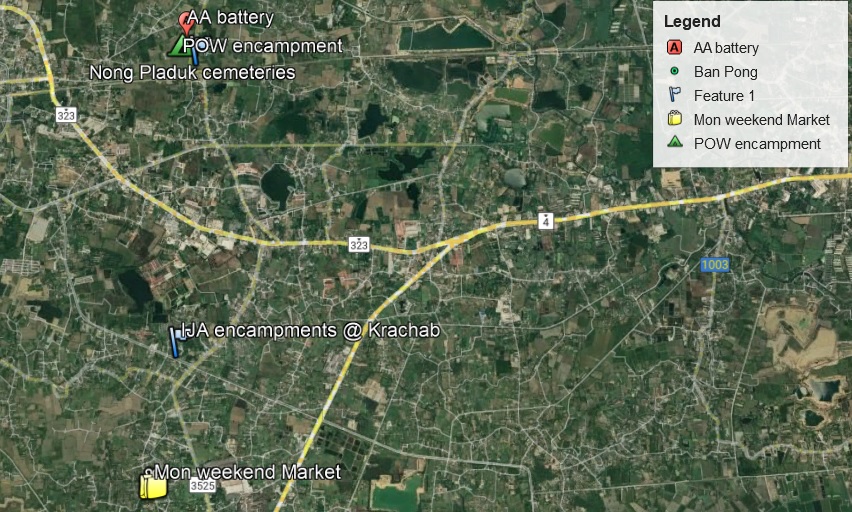

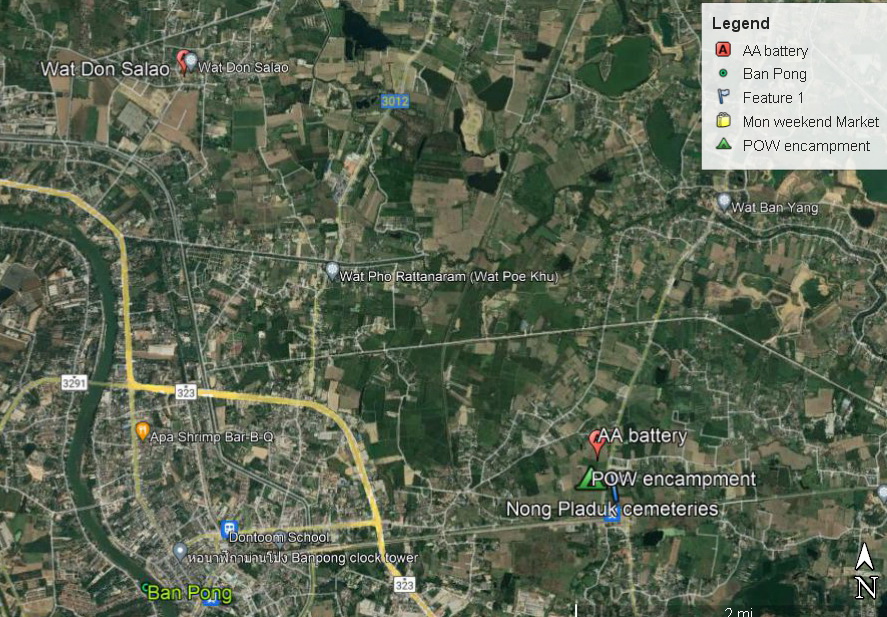

Next, we drove to the north side of the railhead and found an 80yo old man nicknamed Boon plowing[1] a sugar cane field on his tractor. We showed him an aerial photo of the area and he confirmed that:

- Just to the north of the current station was one portion of the POW housing area. That patch of land belonged to another man. The area he was plowing was immediately to the north and just a few hundred meters farther he confirmed that the current sugar cane field contains a large number of circular area that area shown in the photo as being an AA-battery emplacement.

- He was born and raised in that area and had worked this patch of land for many years. He claimed not to have found much in the way of identifiable artifacts, but that there were pieces of metal that were perhaps remnants of the tons of bombs that were dropped on the railhead (about 100-150m to the south). He also stated that he believes that various shell casing and or bullets have been found but that all would have been sold as scrap metal rather than being preserved for history.

- He gave his contact info and permission for the TBREG group to return to walk the newly plowed land with a metal detector.

- As we were about to move on, the owner of the adjacent property drove up and he too agreed discuss access to his land. But that area was currently laying fallow awaiting the next sugar cane crop so it was quite hard packed. He said that he planned to plant a new crop there in the coming months and agreed to further discussions about access to what is undoubtedly a POW encampment.

- Across the road to the east, is the area labeled as a POW cemetery as well as other POW-era structures. These two men were amenable to introducing the TBREG crew to the owner of that land as well.

[1] We were there in the middle of the sugar cane harvest period. So sections of the area were already cleared while most was covered in 2-3m high cane awaiting this year’s harvest.

We then departed NongPlaDuk and headed for BanPong.

Our first stop was a return visit to Wat Dan Toom. Just two weeks before, I had located the clock that had been a gift to the temple from Japanese soldiers who in the 1990s erected a memorial chedi to some of their fallen comrades. [see Section 11.7] On that visit, we could find no one with the key to the room housing the clock. Today, we were infinitely more successful. Not only was there a lady there with access, but she called to the current Abbott of the temple and he came to meet with us. He was able to clarify most of the questions that we had as a follow-up to Professor Boggett’s articles mentioning this temple. As he sat beneath the clock in question in the public area of his quarters where he received guests, he told us the following:

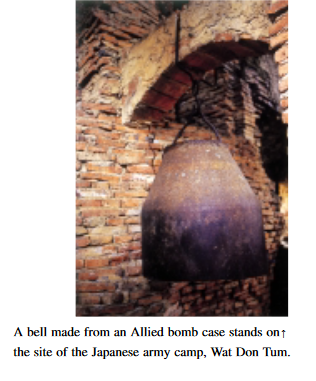

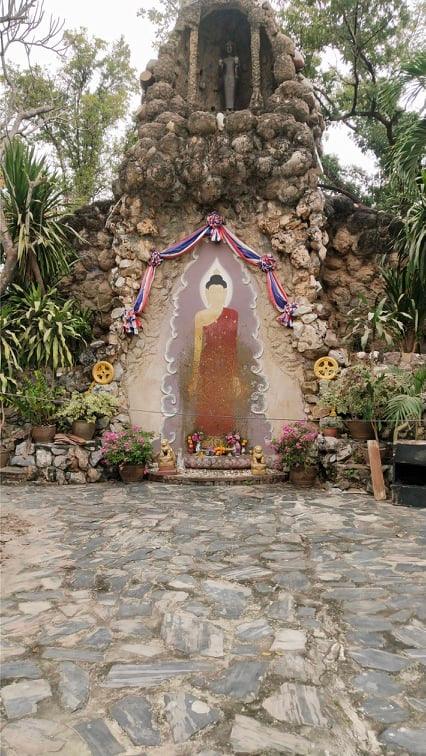

1) There had indeed been a bell that fabricated from an unexploded bomb. That bell had been stolen from the temple grounds some 20 years ago (an unsolved and dastardly crime). The grotto on the far edge of the grounds had been it home.

2) We further inquired about Prof Boggett’s report that there was a building on the grounds donated by a group described by him as the Katsuda War Bereaved Families from Hitachinaka. The abbot clarified that they was not a separate and distinct building but that this Japanese group had contributed significantly to the construction of what is now the main temple sanctuary (bot). Immediately adjacent to that building is the chedi erected in the 1990s by the Japanese soldiers.

3) He was able to confirm that the monk / novice involved in what is known as the BanPong Incident, was associated with this temple and he re-iterated the story as told in Section 20.3.

4) We asked if the temple had any actual documents related to any of these matters or the clock itself. The Abbot denied any direct knowledge of such, but accepted our contact information and said he’d inform us if anything could be found. No one else had ever posed this question to him.

5) As were about to depart, we asked if there were any artifacts on the temple grounds. He denied any knowledge of such then he turned and spoke quietly to his assistant. That young man left the room and returned a few minutes later with a truly amazing ‘find’. Perched on a small display pedestal and encased in a cloth sheath, was a war-era sword! If local lure is correct it belonged to one of the transient camp Japanese officers, if not the Commandant himself. The Abbot claimed that that officer had committed ritual suicide[1] at the end of the war and the temple retained the sword since that time. It was not on public display and in fact was kept in the Abbot’s private quarters.

[JAN 2022 Update 1: some comments on this sword suggest that it is NOT a Japanese Officer’s sword as the story was told. We will continue to investigate its origin. As noted, it had no discernible marking. ]

[ JAN 2022 Update 2: We provided a donation to the temple accompanied by the following note:

A contingent of 23 US personnel included 7 Merchant Marines from the SS Sawolka as well as others who had initially been left in hospital in Singapore as the various US groups passed through there were sent to the TBR as part of H-Force in May 1943. These US POWs were the only ones to travel to the TBR by train and therefore they would have passed through the Wat Don Toom transient camp.

In addition, Flying Tiger pilot Charles Mott (technically a civilian) was shot down over northern Thailand but eventually found his was to the NongPlaDuk POW camp where he was put in charge of moving supplies by truck from there to Kanchanaburi.

This donation is made in their memory by members of the US Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 9951 Bangkok

At the same time, the Abbot provided us the name of a local man who had written a book about his father’s experiences during the war and it reportedly contained the story of the sword. We will follow this to see where it leads. He also said that he had his assistant searching for any existing documents dating to that era or concerning the story of the clock and chedi.

From TS:

On December 31, 2021, he had the opportunity to travel to Don Toom Temple and met the Abbot who brought out a sword given to Yai Ubon by a Japanese military officer.

The history of this sword, as far as the Abbot has heard, was that during World War II, Yai Ubon knew a Japanese army officer. When the Japanese side lost the war, he decided not[1] to kill himself and before returning to Japan, he gave the sword to her.

Yai Ubon nearing the end of her life, knowing that Don Toom Temple has a project to build a museum, gave the Abbot the sword.

[1] differing versions of the sword’s history may be due to narrator’s knowledge or to differences in translation. We are working to uncover the true history of this artifact.

6) The assistant then led us to the grotto on the far side of the temple where the bomb-bell had been housed. Although this area appeared to be quite old, it was currently undergoing renovation / preservation. He denied any knowledge of any other artifacts located in the area.

[Prior to leaving the grounds, I took the opportunity to place the VFW 9951 poppy wreath at the ‘Gate to Hell’ (my words). While the vast majority of the US POWs worked the TBR in the Burma-sector. The Merchant Mariners and other POWs in Group H made the trip from Singapore by train and would have passed through that gate into the transient camp on their way to Hintok. The wreath was placed in their honor, if only briefly for remembrance of their ordeal.]

See Section 11.7 for the full story of this temple’s place in the TBR story.

We then proceeded into downtown BanPong itself. In an old wooden framed housing area immediately adjacent to the BanPong to Singapore tracks, we found our next elder storyteller.

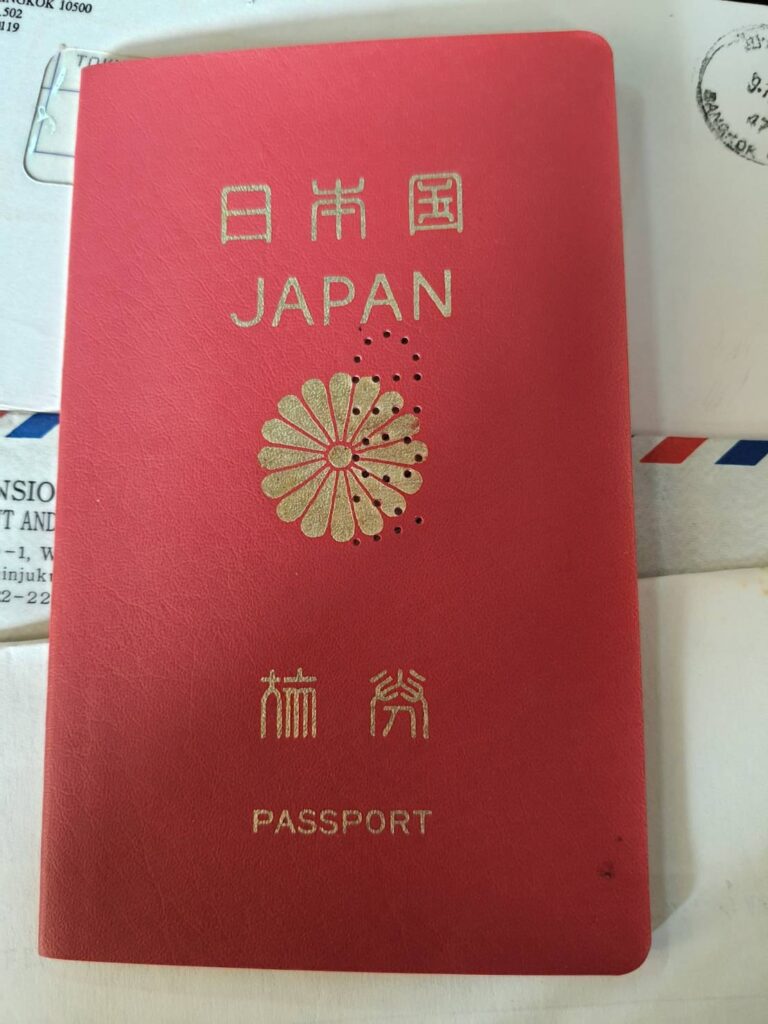

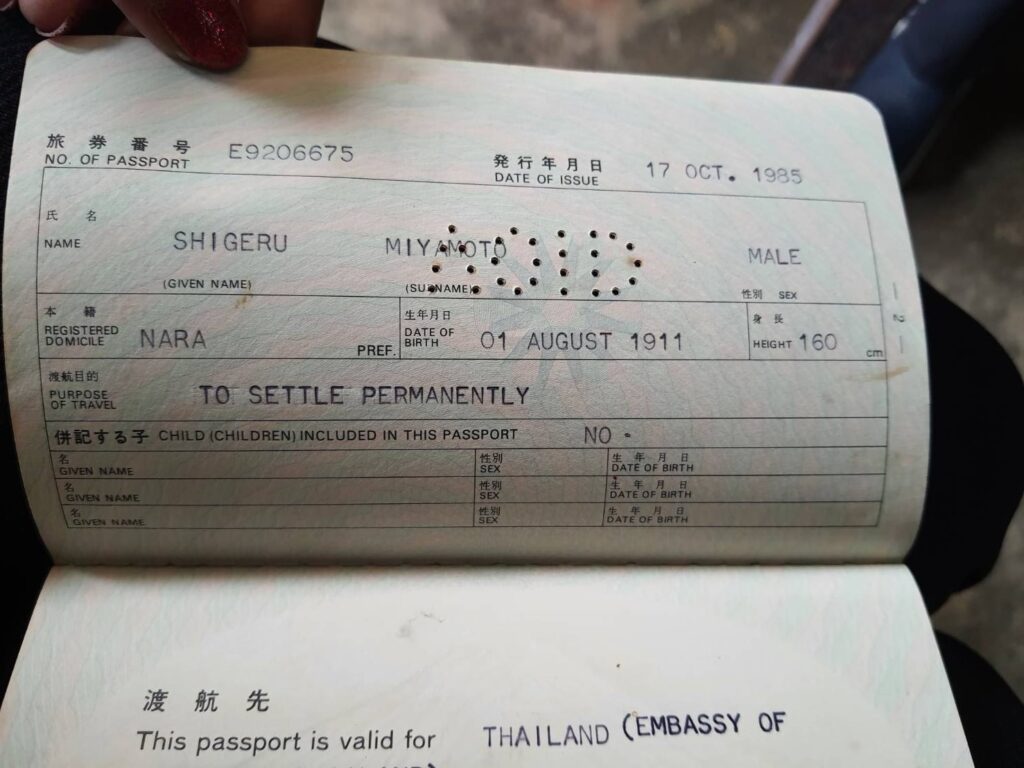

She is Sumalee Chatwutichai[1], a 72yo (DOB 1948) daughter of a Japanese soldier and a Chinese mother. She related her family story this way:

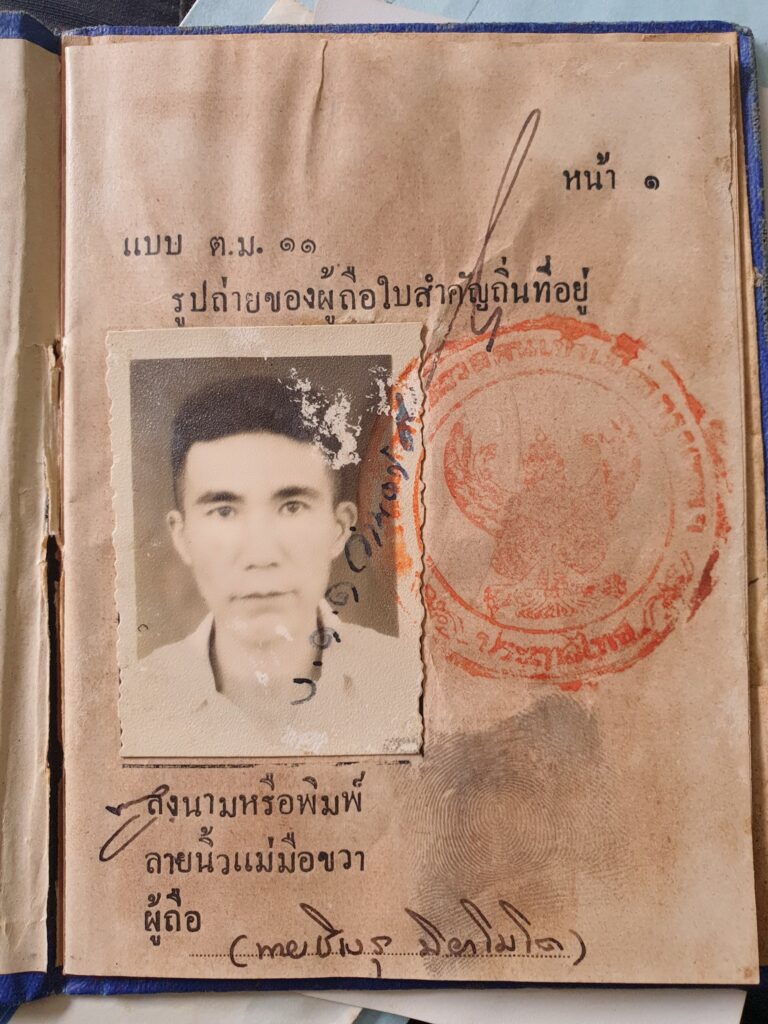

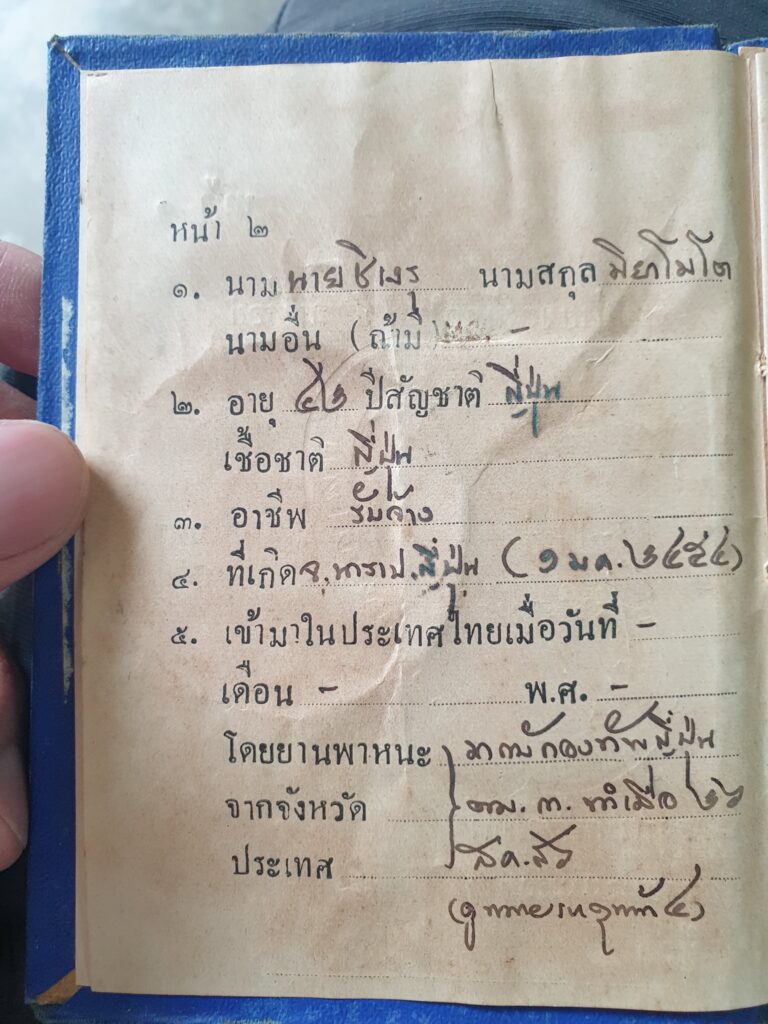

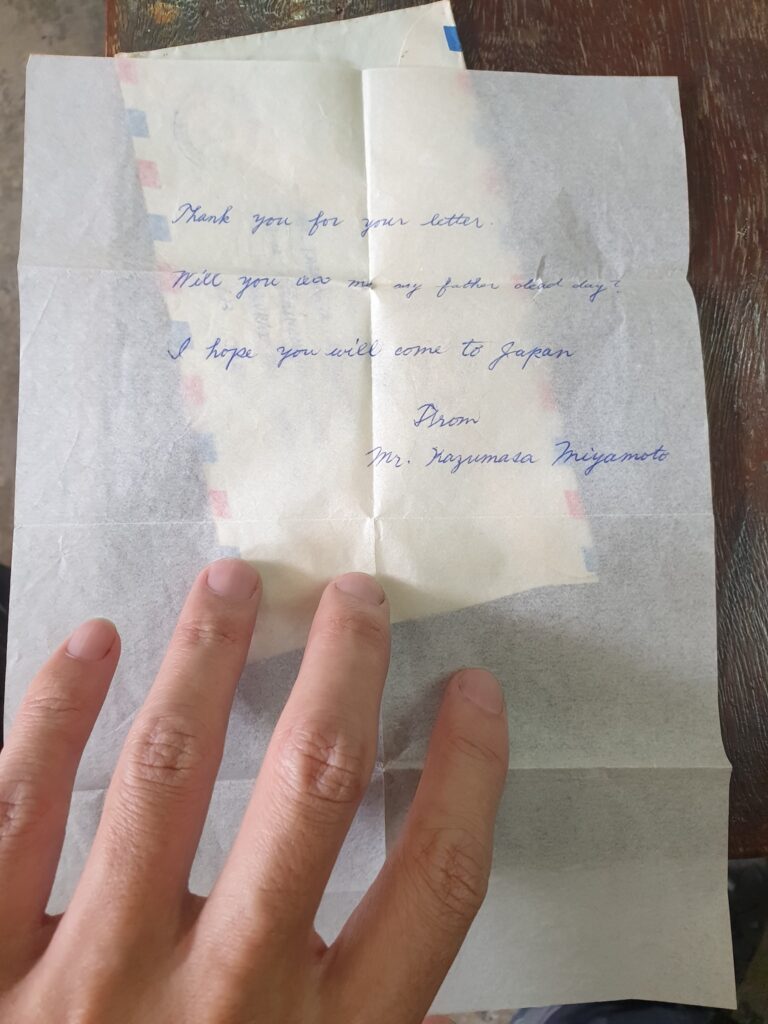

- Her father, Shigeru Miyamoto, was indeed a member of the IJA stationed in BanPong. He was a cook and met her mother who was one of the locals who provided vegetables and the like to his cook house. As the war ended, he and apparently quite a few of his comrades decided not to return to Japan but to start a new life in Thailand. Her father had been born in 1911, so he was in his early-30s when he arrived in Thailand; old enough that he had left a wife and son in Japan.

- Having decided to stay, he married his widowed Chinese girlfriend. Sumalee was their only daughter. Her father worked most of his life at the nearby St. Joseph Catholic Church and school, hence the name he had adopted as shown in the photo, Joseph.

- She also produced a number of official documents relating to the pension her father received and some interactions with the Japanese Embassy in BKK. These documents included his passport and official Japanese identity papers.

- Unfortunately, she had spent a portion of her early life living with other relatives and she could not relate any deeper stories concerning her father’s war-time experiences. Her father never spoke of his wartime experiences nor did he teach her any of the Japanese language.

- Her existence in and of itself relates to another untold story of the era: that IJA soldiers decided (refused?) to return to their homeland and began life anew in Thailand. Perhaps the Japanese Embassy could share some information on this untold story.

[1] She explained that in order for her to exercise her full rights of Thai citizenship, she had had to adopt a Thai Surname rather than use her father’s family name.

Our final stop for the day, was on the south side of BanPong at Wat Don Krabeung. There we met with 93yo Khun Samroui Srihajrak.

- He explained that during the war all the local schools were closed, so he and his ‘partners in crime’ ranged all over BanPong but were most familiar with this southern sector.

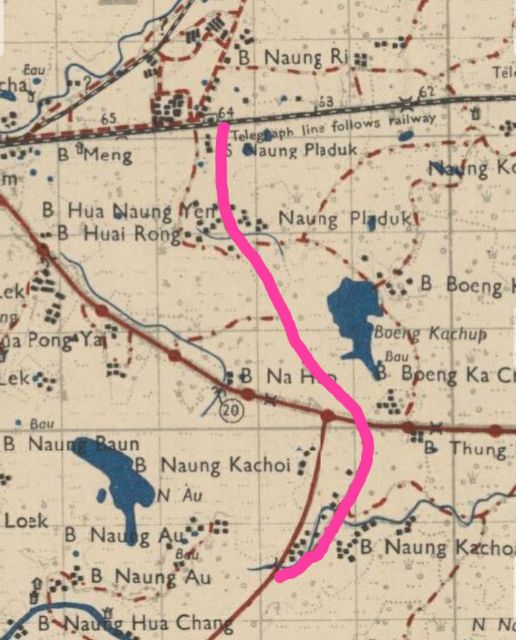

- We showed him a map of the area that depicted a number of spurs to the TBR that do not exist today. He remembered almost all of them. Apparently, one of the longer spurs was the one that passed the workshop area that we had visited near Wat NongPladuc. It ran a few kilometers south from the railyard to the area known as Ket Krachab.

- According to him, there was thousands of IJA soldiers encamped in that area roughly 7-10 km south of NongPlaDuk. He places them there in 1944-45, so it is highly likely that these were units who had retreated from Burma via the TBR and were encamped awaiting further orders.

[His memories were the first confirmation that we have obtained of the location of a rather significant number of IJA combat troops in this area.]

In the past, during World War II, there was a railway line that separated from Nong Pla Duk Station and headed south. According to the data studied by foreigners, in the postwar period, the railway was dismantled, and then a road was built on the railway. The road that passes in front of Wat NongPlaDuk converges on the road # 123.

Khun Samroui said there was a railway line in front of Wat Nong Pla Duk and that the railway would cross the road # 123 at the PT pump station area, then run south and converge with the old Petchkasem Road south of the Municipal Office of Tam Krachak. It appears as if Soi Prachang was that road built over the railway embankment.

======================================

In his book, 1000 Days on the River Kwai, British Ltc H.C. Owtram describes how his men laid tracks in the NongPlaDuk-BanPong area. He was in Group #1 that arrived from Singapore in JUN 42; before the official start of the TBR. Since it is generally accepted that Thai workers built the initial 50+Kms to KAN, we might assume that Owtram’s group worked on some of these spurs that the Japanese Engineers added to existing rails. He does not provide details as to which section of the TBR he worked.

https://www.tracesofwar.com/books/2908/1000-Days-on-the-River-Kwai.htm

================================

Here is another similar interview posted by Thansawath Saranyathadawong:

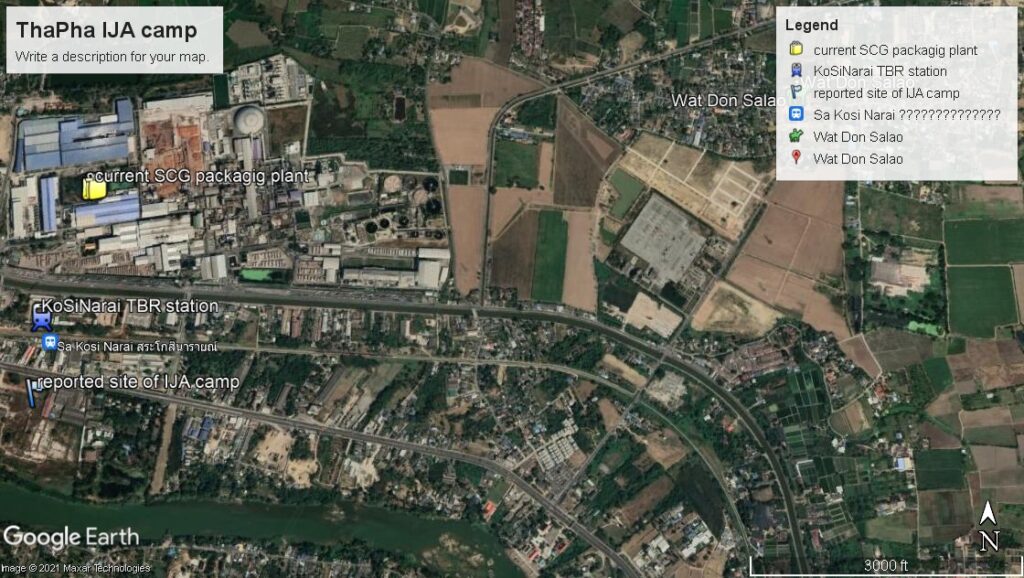

Khun Warm Sakarak (ยอุ่น โสดารักษ์; now 88yo) was born and raised in Don Saloa Village a few kilometers NW of the NongPlaDuk railhead. She saw Asian (Tamil-Indian?) romusha workers passing through the Tha Pha area, hungry, asking for vegetables to eat, and she brought them peppers, turmeric and bananas.

Near the end of the war, Allied aircraft began bombing the NongPlaDuk Railyard. Before bombing, Allied aircraft would drop flyers. The message outlined a list of Japanese camps that were to be bombed and warned the local people to stay away. She also said that residents of the area had to cook for food and finish their meals before 5 p.m. Because at night, no lamps or fires were allowed to prevent bombing.

She said that she could look from Don Sela village towards Nong PlaDuk and see the allied planes dropping bombs at night.

Allied aircraft drop luminous flares attached to several parachutes above NongPlaDuk Station (dropping flare illuminates so bombers can see targets), and then loud bangs as the bombs were dropped on the NongPlaDuk area.

She also said that what was shocking to Japanese soldiers killing horses after their use in bulk work. The objective was not to allow the horses to be taken by the Thais. Killing the horses starting with the Japanese soldiers digging deep holes then shooting horses one by one, some were pushed into the pit alive, and all the horses were buried at the entrance to Don Salao Temple, She said she remembers exactly where they were buried.

She also described that in front of the large SCG paper factory on the near Luk Kae was one of the Japanese military camps. This is a few more kilometers to the NW of her village.

JAN 2022 Update to the barrel artifact at #5 in the Khun Boakai story above:

A post on the TBREG FB page dated 26 JAN shows similar barrels that contained cement/mortar that were damaged in shipping and solidified the contents.