Update OCT 2023:

There are some who refer to this obelisk as the “un-named pagoda” which I had thought was a strange name. It turns out that it is just inverted! Recently, the temple’s abbot told us that it is called Chedi Niranam which could translate as as “grave of the unnamed”. “Niranam” is the Thai word for unknown or anonymous. It is simply a reflection of the fact that as they were buried and when the obelisk was added (1957), no one knew who these remains belonged to.

So Chedi Niranam it shall be!

===========================

While the Thai-anusorn Shrine constructed by the IJA camp guards and Allied POWs was dedicated (in 1944) to the Asian forced laborers (romusha) and Allied POWs who died while building the TBR, it remains one of the least known and least visited sites of the TBR story.

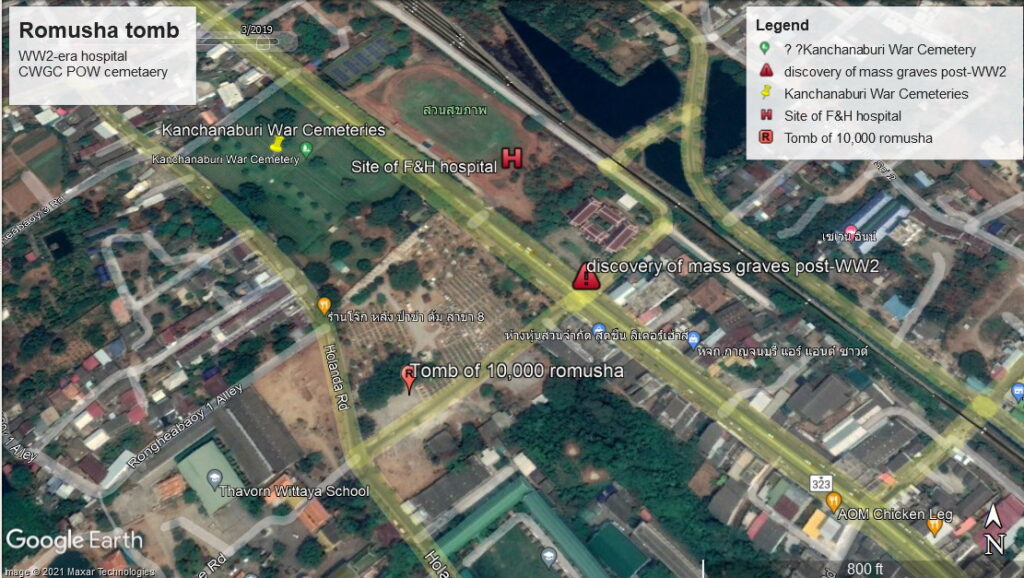

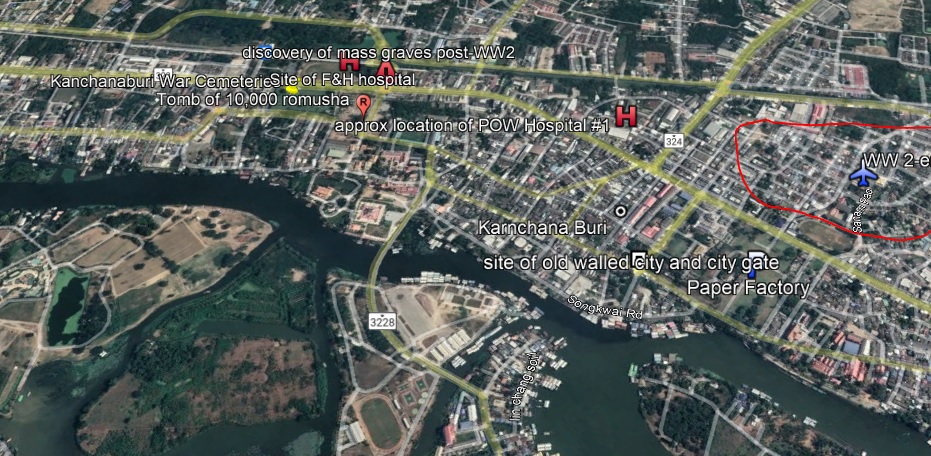

Perhaps a more meaningful site exists that is known only to a select few aficionados of the TBR. Immediately adjacent to the Don Rak CWGC POW cemetery is another cemetery that dates back hundreds of years. That sacred piece of land is small; perhaps 2 acres and contains hundreds of family graves in both Thai and Chinese style.

It is owned and maintained by the staff and monks of Wat ThaWorn Wararam. Outwardly, the contemporary buildings are a mixture of traditional Thai and Chinese style architecture. But these are mostly of rather recent construction; all post-WW 2. This temple is locally known as Wat Yuan which is the Thai slang word for people of Vietnamese ethnicity. The Vietnamese name is Kan Taw Ter.

This temple is said to have been established in the early 19th century during the reign of the Thai King Rama III (1824-51) by refugees that had flew to Thailand from today’s Vietnam. These people had established a small settlement on the banks of the Mae Klong River only a few kilometers upstream from the walled city of Kanchanaburi. Local lore also states that King Rama V (Chulalongkorn 1853-1910) was traveling up the Mae Klong River when his attention was drawn to the chanting of monks on the river bank. He stopped his flotilla and went to visit with them. It was then that he granted them royal patronage and named the temple Wat ThaWorn Wararam.

Fast forward then to the WW2-era. The area immediately to the north of the temple became incorporated into the southern end of the huge POW camp known as ThaMarKam where the Allied POWs were consolidated after completion of the Thai-Burma Railway. At that time the temple grounds extended about a kilometer inland from the river bank. Viewing it today, those grounds would include the current temple proper, the adjacent cemetery and continue across what is now SanChuto Road – the main thoroughfare of the running through the city of Kanchanaburi.

In 1943-45, the Allied POW camp ran from the TBR tracks and bridge eastward almost to the site of the current CWGC cemetery. Directly across the roadway from that cemetery there is currently a large sports field was reportedly the site of one of the many hospitals in the area (see map above). Once the first 50 kilometers of the TBR were completed, the Japanese moved their HQ for the TBR from BanPong to ThaMarKam. So most of their support base was located there from late 1942 until SEP 1945.

The temple grounds adjacent to that sports field was the northwest end of a large section of the camp that housed the multitude of romusha who were also consolidated from their work camps strung along the length of the TBR. That camp extended east to approximately where the Japanese aerodrome was built; that area today is best found as between the current rail line and Sangchuto Rd behind the Red City market. While there were other nationalities present, the vast majority of these romusha were ethnic Tamil-Indians. Records indicate that there were Chinese from Singapore and Javanese at this camp as well as some Vietnamese. Most of the Thai and Burmese slave laborers had simply melted back into the jungles and were never housed at this camp in any large numbers.

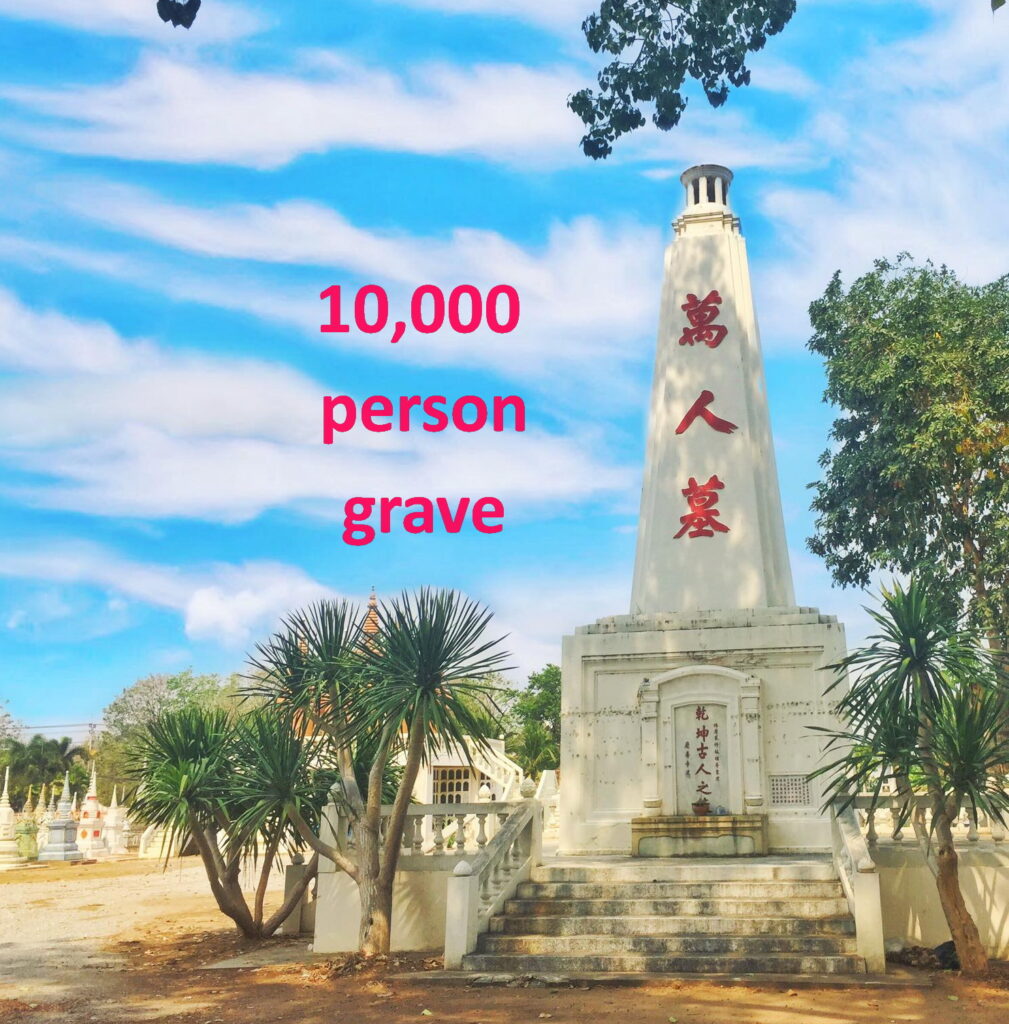

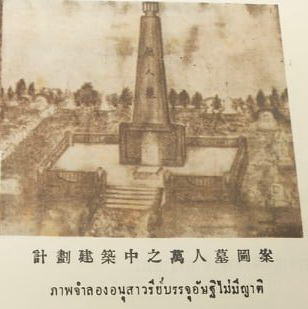

The relationship between Wat Yuan and these romusha came to the fore-front in the immediate post-war years. As construction of the current SangChuto Rd proceeded, mass graves were uncovered on what had been temple grounds. Here the story is a bit lacking in detail, but apparently the Abbott took responsibility for those remains and reburied them in the existing cemetery on temple grounds. According to local lore, he had a large obelisk erected over the tomb of as many as 10,000 sets of remains and ashes. So the 3 characters on the obelisk translate to “The Grave of Many People”. The longer inset inscription can be translated as “The Gravesite of Males and Females Who Have Died”, or something similar with the date 1957 (BE 2500) in the right column.

The three characters are 萬–10,000, or all or every, 人–people, 墓–grave. So, it is most likely not exactly 10,000, but many or an unknown number of many people. “Erected by the Chingshou Temple” The two characters “ching shou” could be translated as “celebration of life”. This is the name on one of the newer larger Chinese style buildings on the main temple grounds.

Dated 1972, this smaller insert displays the names of eight people, followed by an amount of Thai baht. The two columns on the right indicate that these eight people helped in the repair and cleaning.

UPDATE APR 2024:

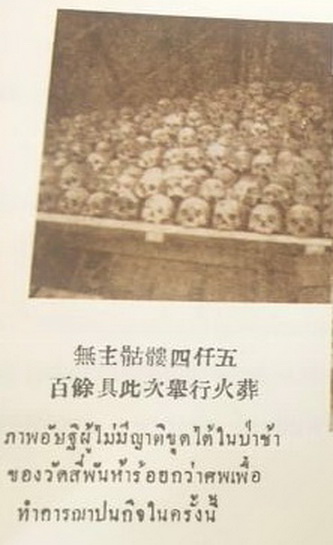

The question is asked as to what (not who) is buried in this grave. We have only one photo whose origin is lost to history. It was published in the 150 Anniversary book of the temple and shows a display of skulls. But in the last line of the caption, we are told that these were cremated before being buried in the 1950s.

I think that the most important fact shown here is not that the grave contains cremains but that the original 1950s discovery was of bones not cremains. My thanks to Thansawath Saranyathadawon for pointing out this fact.

============================================

Another interesting, and possibly historically significant, item is that immediately adjacent to the obelisk are two large Bo trees which may very well qualify as witness trees dating back to the POW-TBR era.

Update Dec 22 2021: [edited for accuracy from the original Thai text]

On December 21, 2564 13:00 N.P.A. (special)

Dr. Surin Chanpian, President, Deputy President of Kanchanaburi Tourism Business Association welcomed Dr. Silva Kumar , Dr. JJ Karwacki , Mr. Elangovan Govindasamy and the DRIG team on the occasion of coming to discuss ways to create a memorial for Malaysian workers who were part of the Asian Forced Labor to build [a bridge over the River Kwai] the Thai-Burma Railway.

During World War II, to tell stories in those days at Floating Food Raft, Tha Makham Subdistrict, Mueang District, Kanchanaburi Province, after that, Col. (Special) Dr. Surin Chanpian, along with Mr. Setthawit Akkarakitwarasakul Deputy President, Kanchanaburi Tourism Business Association led Mr.Silva Kumar, the representative of former Malaysian workers, and his group met Phra Samana Namtheerachan, Permanent Secretary of Rights, Abbot of Wat Thavorn Wararam (Wat Yuan) to ask for advice on getting assistance in creating a memorial to commemorate their ancestors.

Malaysians then known as Malayans. The Japanese soldiers enlisted mostly Tamils to join in the construction of the railway. During World War II, Dr. Silva Kumar revealed to reporters that his father was one of those Malaysians who were recruited by Japanese soldiers as labourers to build the railway. During World War II, his father served as a cook for Japanese soldiers for almost 3 years. Later, his father and those workers walked back to Malay. It took between 6 to 8 months.

Dr. Silva Kumar added that the journey to meet Phra Samananamtheerachan, permanent right, abbot of Wat Thavorn Wararam (Wat Yuan) this time was to trace the past of his father and those workers and that he would like to ask for help from the Abbot to create a memorial that tells the story of his father and the laborers who worked in the construction of the railway so that Malaysian children [and the world at large] can come to respect and remember their ancestors and their sacrifices. After discussing and asking for the advice of Phra Samana Namtheerachan, Dr. Silva Kumar and the group received the kindness from the Abbot to be able to improve the existing international monuments ( obelisk) on behalf of Malaysian workers for Malaysian children to know the story that happened in those days and to join in the remembrance of their ancestors.

It made me feel very happy and thanked the abbot of Wat Yuan and Colonel (Special) Dr. Surin Chanpian is giving us this place . “Thank you very much giving us advice on how to go about it”.

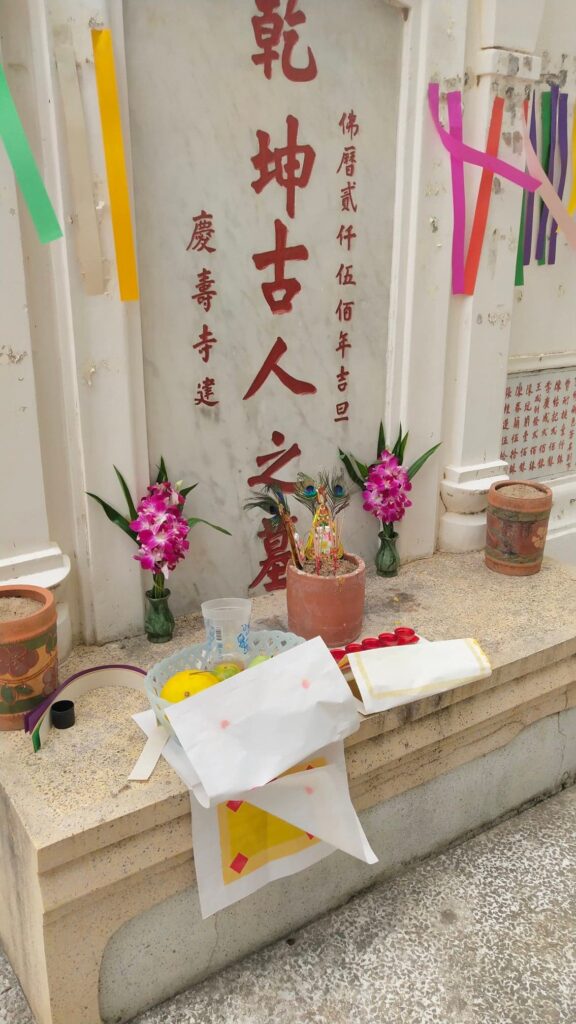

20.5.1 Annual Qingming Ceremony

Annually in April, the Chinese community honor their ancestors with food and offerings. The cemetery associated with is temple is a mix of Thai, Vietnamese and Chinese style graves. On behalf of the DRIG, I attended the 2022 ceremony in hopes of learning more about the origins of this memorial. Unfortunately, that was not to happened. The temple elders (as old as 90) that we spoke to knew only the basics of the story and a few had quite mistaken ideas that there may be ‘Japanese soldiers’ buried therein (not true).

All in all, it was a slightly disappointing day as to gathering new information. One elderly gentleman confirmed that it had indeed been built in 1957 and volunteered that it had been renovated in 1972. But he knew no more. The 1972 date was then attested to by another. Neither was sure just what had been done then. We do have a drawing from the mid-1950s that purports to show the obelisk as it is to be built. Note the single set of steps to the terrace as opposed to the 4 sets that exist today. Was this the renovation? Why?

As part of the Qingming ceremony, the temple elders gathers in front of the obelisk to make offerings. They struggled to explain the connection between honoring Chinese ancestors and this particular grave dating back but 80 years. It seems that it is something that ‘has always been done’ and they are just continuing the tradition. As stated above, many were not quite sure who was buried therein.

As the only westerner (farang) in attendance, I was greatly honored to be invited to join the elders in the ‘offering line’. My probing questions and my knowledge of the memorial and even the tradition of the Qingming ceremony seemed to impress them.

Word seems to have ‘leaked out’ that there was a group (they weren’t quite sure who) was interested in renovating and re-dedicating this memorial. As a group, the elders seemed quite in favor of the concept. as per the DEC 2022 report above, I’m sure that they will be quite impressed with the DRIG plan to tell the story of the Tamil romusha who are interred here. I’m looking forward to seeing many of these elders again, when the re-dedication ceremony is held. I’m quite sure they will be there with great enthusiasm to learn the story and assist in its launch.

The markings on the obelisk walls were obviously from many prior such ceremonies over the years. We finally got to see the reason those smudges exist.

I have yet to ascertain the precise significance behind these ribbons.

Other images of the family gatherings and offerings at the obelisk: