1.3a What is the TRUE STORY?

What is the TRUE STORY of the Thai-Burma Railway?

Is it one of the successful completion of a massive construction project?

Is it one of cruelty and brutality that one group meted out on others?

Is a story of survival under the most adverse of conditions?

Is it a story defined by geography or engineering? Is it a documentary or a story of personal struggle?

How does one tell the story? Is it the tale of faceless groups of uncounted men who toiled, died and survived? Or is it to be told through the eyes of individuals as Hollywood would seemingly do it?

Is it all of the above?

Perhaps this is one reason why the story is not oft told. There are dozens of YOUTUBE videos that flash period pictures or clips of the scene as it stands today. They are most often un-narrated or contain incorrect information spouted by someone with no idea as to what truly occurred when and where.

Where does one turn to learn the TRUE STORY? All of the books and movies; all of the photographs and post-war film provide only a glimpse of the full saga. None can tell the whole story. No one person experienced more than a limited perspective. The best known story is portrayed in the movie: Bridge on the River Kwai. Too bad it is horrible history. The director of the movie To End All Wars took a stab at telling a wider story. He created a fictional group of POWs then placed them at various places and had them experience some of the more common situations as related by the POWs themselves.

61,000 Allied POWs and as many as 500,000 Asians were the tools that built the Railway and a number of associated projects. That any, much less most, survived is a miracle unto itself. How does one integrate a story of geography, engineering, personal horror, disease and death, survival and liberation? Apparently, not easily for few have tried.

The original JEATH museum (at Wat Chai Chumphon) was seemingly the first attempt to portray the POW experience. This was followed by the Thai-Burma Railway Centre [ www.tbrconline.com ]. Founder Rod Beattie is probably the world’s leading expert on the TBR. That museum undoubtedly tells the most comprehensive story of the TBR found anywhere.

Another problem is answering the question: Whose story is it to tell? The Japanese Engineers would tell a story of a magnificent engineering triumph. A military historian would cite its failure to assist the IJA in successfully invading India. The Allied POWs and romusha tell it from an entirely different perspective. All are correct and none complete!

Herein, my initial effort to preserve the story of the US POWs who worked the TBR grew over time. I came to the realization that nothing exists in a vacuum and that to more fully understand what happened to that small group of men, one had to set it into the context of the entire Southern Pacific Theater of WW II. From the invasion of Java in search of oil and other resources through the consolidation phase post-construction and operation of the Railway, we can follow the deterioration of the Japanese plan to invade India.

Summarizing the building of the Railway in a few hundred words is not that difficult. It did, after all, take place over a period of only 15 months; a blink of the eye even in the context of the Pacific Theater. Yet, in doing so, we lose the richness and horror of the greater story. Hundreds of thousands of men (and some women) were reduced to the role of tools used to achieve a specific end. How does one convey how they were stripped of all humanity and then discarded in the jungle when they were no longer useful?

Finding the proper way to relate the TRUE STORY of the TBR is no easy task.

1.3b A controversy

In the 2000s, a controversy of sorts arose concerning the telling of the story of the TBR. The question had arisen in the social sciences literature as to who has the ‘right’ and perhaps then the responsibility to keep the story alive for future generations. Indeed, the saga of the TBR holds a unique position in history. For the Thais it is not particularly accepted as a part of Thai history. It was after all perpetrated by one group (Japanese) on other groups (Allied POWs and laborers from other nations). The Thais had only a brief and relatively minor direct involvement spanning SEP-NOV 42.

As we rapidly approach the 100 year anniversary of these events, the question arises as to whom should preserve the story for future generations. The events occurred in Thailand (and Burma) but is it truly part of Thai history? These events were perpetrated by the Japanese but would they want to re-open the wounds of that era? The victims were citizens of many nations. Is any one of them responsible for keeping the story alive? [see Section 29 for an expanded discussion on this topic]

Over the ensuing years, the original story tends to get more and more ‘sanitized’ as it is retold. The three museums that depict events and display artifacts of the era do so in a manner more acceptable to the 20th century sensibilities of the tourists visiting them. Even so, there is a fourth ersatz museum near the bridge that has the audacity to display human remains in a for-profit enterprise!

The three war graves cemeteries that hold the remains of the Allied victims of this period of history (some 12,000 in all) are administered by the London-based Commonwealth War Graves Commission. But they have a world-wide and multi-conflict responsibility. They could hardly be expected to contribute more than a basic description of what their few acres of land contribute to the story. Aside from a small memorial museum located at the cemetery in Burma that few are physically able to visit, there is very little background given to the graves that they maintain so meticulously.

At the site of the famous iron bridge, there are two small memorials that are all that directly link the bridge to events of the era. One is a depiction of the route of the TBR located to the left of the bridge. The other is the 1997 memorial to the US POWs placed by the US Veterans of Foreign Wars organization. Other than these, there is little to historically link the surviving bridge to events of the past. Few of the selfie-taking tourists ever seem to even notice them.

So we return to the question of precisely who should have the right and the responsibility to relate the background story of this surviving artifact of an almost century-old story. Who precisely does this story belong to? As noted, it is not truly a piece of Thai national history. They had only a supporting role in the events overall. Other than continuing to promote tourism, they have no true responsibility to relate to larger background story of the popular bridge. One must also ask the question about the true level of interest of the current day-trippers in knowing why this is such a popular place to visit. Do they really want to know the history behind the bridge and the rails that cross it? Seemingly they are quite content to take selfies and buy refreshments and souvenirs before returning to work or school on Monday morning; as ignorant of the history as before they arrived.

The largest number of graves in the war cemeteries belong to British POWs followed by Dutch and Australian. The remains of the US POWs were all repatriated by 1948. Nearly a century on, the other category of visitors to this area are descendants of those who lived, worked and died here. Soon none of the POWs themselves will be alive to even contemplate a visit. So it is for their descendants – now more likely grandchildren – to make the pilgrimage to visit the site of their loved one’s ordeal and perhaps his grave. But such a group would seemingly have made an effort to educate themselves as to events of the era. They can seek specific information related to their loved one from any number of sources. Their quest for information would be somewhat more targeted to that person’s experience rather than to the wider story of the TBR in general.

There are still a large number of TBR-related organizations many of whom maintain websites as a means to perpetuate the memory of their specific members involved in this tiny episode of world history. But almost by definition, their focus is limited to one military unit or in some cases a specific individual. Each such place of remembrance is what I envision as a tiny piece in a large jig-saw puzzle. The larger, fuller, deeper story of the TBR can only be appreciated when all the pieces are assembled into a more comprehensive picture.

The same is true of the host of books published by POW survivors. Necessarily, they present a tunnel-vision perspective. Woven together they, too, add clarity to the larger story. But as time progresses more and more are falling out of print for lack of interest. They will soon be doing little more than gathering dust in libraries around the world unread by the users of that facility more likely seeking internet access than a history lesson.

There are seemingly few individuals like the founder of the TBRC in Kanchanaburi, Rod Beattie, who are willing and able to dedicate a lifetime and personal fortune to preserving the memory of this period of history. But in recent years, he too has distanced himself from the organization he founded and has returned to Australia. He more than anyone is responsible for launching me on this quest to preserve the story of the US POWs that has now expanded exponentially to encompass the larger story.

So a subsidiary question as to who has the right and responsibility to preserve this story is who would be the potential audience. Descendants are more likely to be interested in the person-specific data provided by the TBRC staff upon request. Their focus is on serving that niche. In support, they have complied a huge dataset of details of individual journeys. They are very good at what they do, but other than the static displays at their Centre they do not seem to be analyzing their data with a view to relating or expanding the larger story.

Scholars and students of history would be a potential audience for this larger story of the TBR. But in what medium? I present an electron-based story accessible by any who wish to search for it. The eminent history professor David Boggett did amazingly unique and detailed work particularly on the segment of this story pertaining to the romusha. His work was published in the journal of a rather obscure university in Japan and I dare say is not widely accessible or read. I obtained access only by a targeted request to the university staff. When history books even deign to acknowledge that this event occurred, it is usually presented in a few sentences if even a paragraph. In many ways, despite the tens of thousands of lives taken and lives affected by this Railway, it is a mere blip on the timeline of even the war itself.

Although it was not intended as such at its outset, my quest (since 2016) to relate the story of the 1% of the TBR victims who were US veterans has expanded to set their story into the context of the world events at the time and the TBR specifically. Their story as they took their own unique journey across Burma and Thailand can only be appreciated fully when placed into the context of the POWs of other nations that labored beside them. And even the full story of the TBR must be placed in its proper place in the context of what was happening at the time to drive the need for such a monumental effort.

In summary, there seems to be no nation or group that ‘owns’ this story to the extent that they would be assigned responsibility for compiling and preserving the overall story for future generations. It would seem to fall to more focused organizations to attempt to preserve various aspects of this large and complex story. Hence in 2022 there is a new memorial dedicated to the crewmen of the H.M.A.S PERTH about to open in that name-sake city.

Here is an example of the TBR saga as presented by one of the largest and most active organizations that calls itself FEPOW (Far East Prisoners of War). Today almost exclusively composed of the descendants of those POWs (termed COFEPOW or children of the FEPOW; now expanded to include other family particularly grandchildren) :

https://www.cofepow.org.uk/armed-forces-stories-list/burma-siam-railway

It is rather typical of such groups to commemorate (appropriately so) all the men of a particular military unit who perished regardless of where that death occurred. In short, such rosters do not add to (nor detract from) the larger TBR story. They tend to be rather superficial in their treatment of any one aspect of the story because they are mandated to cover the entire Asia-Pacific Theater. In some way I feel fortunate that I stand among a small group of individuals who have dedicated the time and effort to attempt to relate a more comprehensive saga of the wider TBR experience as it played out from June 1942 and into the post-war months in 1945. It is possible that my efforts to compile and analyze information building from by-name rosters of the men who lived and died in this saga in an effort to relate the story supported by available data as to how the TBR was built is a stand-alone work of historic significance.

I do not in any way claim ‘ownership’ of this story and the ‘responsibility’ to relate the story is certainly not mine. None the less, I believe that this work stands alone and hopefully can stand the weight of time as we hit the century mark of this event.

=================

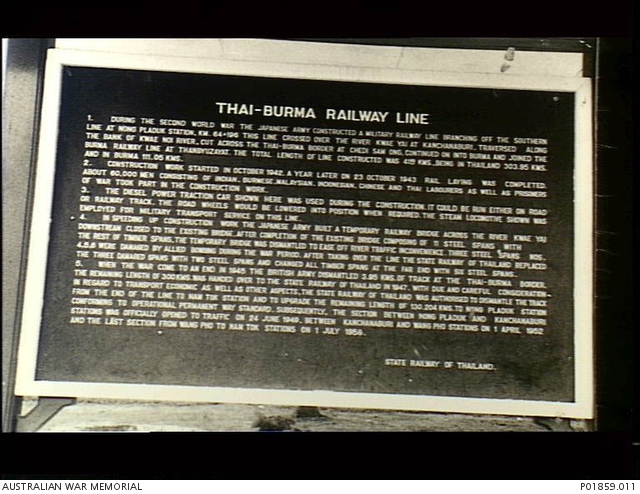

1.3c State Railway of Thailand plaque

This photo said to have been taken in 1973 shows a plaque erected near the Bridge by the SRT authorities.

It would be a rare effort by any Thai agency to relate the historical context of the Iron Bridge.

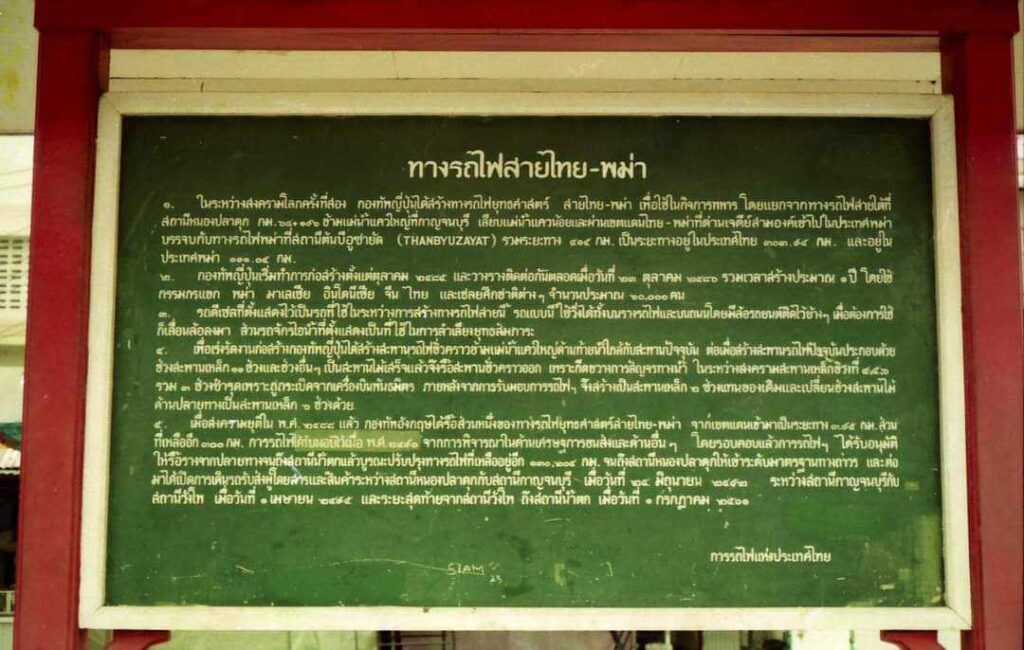

The Thai Version:

The plaque reads:

“Thai-Burma Railway Line.

1. During the Second World War the Japanese Army constructed a military railway line branching off the southern line at Nong Pladuk (also known as Non Pladuk) Station, Km.64+196. This line crossed over the River Kwae Yai at Kanchanaburi, traversed along the bank of Kwae Noi River, cut across the Thai-Burma border at Chedi Sam Ong, continued on into Burma and joined the Burma railway line at Thanbyuzayat. The total length of line constructed was 419 kms., being in Thailand 303.95 kms. and in Burma 111.05 kms.

2. Construction work started in October 1942. A year later on 23 October 1943 rail laying was completed. About 60,000 men consisting of Indian, Burmese, Malaysian, Indonesian, Chinese and Thai labourers as well as prisoners of war took part in the construction work.

3. The diesel power traction car shown here was used during the construction. It could be run either on road or railway track. The road wheels would be lowered into position when required. The steam locomotive shown was employed for military transport service on this line.

4. In speeding up construction work the Japanese Army built a temporary railway bridge across the River Kwae Yai downstream closed [sic] to the existing bridge. After completion of the existing bridge composing of 11 steel spans with the rest of timber spans, the temporary bridge was dismantled to ease off river traffic inconvenience. Three steel spans nos. 4, 5, 6 were damaged by allied bombing during the war period. After taking over the line the State Railway of Thailand replaced the three damaged spans with two steel spans and changed all timber spans at the far end with six steel spans. 5. When the war come [sic] to an end in 1945 the British Army dismantled 3.95 kms. of track at the Thai-Burma border. The remaining length of 300 kms. was handed over to the State Railway of Thailand in 1947. With due and careful consideration in regard to transport economic as well as other aspects, the State Railway of Thailand was authorised to dismantle the track from the end of the line to Nam Tok Station and to upgrade the remaining length of 130.204 kms. to Nong Pladuk Station conforming to operational permanent way standard. Subsequently, the section between Nong Pladuk and Kanchanaburi Stations was officially opened to traffic on 24 June 1949, between Kanchanaburi and Wang Pho Stations on 1 April 1952 and the last section from Wang Pho to Nam Tok Stations on 1 July 1958. State Railway of Thailand.”

It was subsequently removed, likely during new construction of promenades along the river bank. So there exists today no true explanation of the significance or origin of the Bridge.

More from the Thai Tourism Authority:

Unfortunately, a simple internet search for “history of the Death Railway” turns up a few travel sites but no truly authoritative / academic presentations.

============

1.3d the ANZAC PORTAL

Perhaps the most extensive effort to tell the full saga of the TBR, albeit with an Australian perspective, can be found at:

https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/

https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/burma-thailand-railway-and-hellfire-pass-1942-1943

====================

1.3e EXPLORE TBR

Over the past few decades, Kevin Roberts has dedicated innumerable hours to documenting and exploring the path of the TBR. His goal was to provide information to like-minded explorers who might also wish to tread these hallowed paths. But he did much more than film his walks in the jungle. He has combined those clips with extensive research on the engineering and geography of the TBR and traces the path using GOOGLE EARTH and MAPS clips.

My only reservations about this superb collection of information is that he deals purely with the Where, What and the How to the exclusion of the Who and the When as well as the Why. His is a purely geography-based series without a historical context. In the INTRODUCTION episode he contends that the history is adequately presented elsewhere (but without citation of that where). I beg to differ. It is my fervent hope that such an exquisite series could be made that does present the historical context to the TBR.

One additional thought is that for a variety of reasons, Robert’s explorations are limited to Thailand. Hence, we have no access what so ever to the geographical explorations of the Burma Sector of the TBR. By overlaying the history, that deficit could be at least partially filled in.

I approached the author of this series about expanding it to include more of the history. He was unphased. Seemingly, he’d rather document the scars left on the land than the men who were scarred in the making of those scars.

1.3f Not Bataan

Despite what some YOUTUBERS think, the Thai-Burma Railway has nothing what so ever to do with the Bataan Death March! Yes, both took place during WW 2, but Bataan is in the Philippines!

LEST WE FORGET…

1.3f ANZAC Day ceremonies

Originally, ANZAC Day was the commemoration of the WW 1 invasion of Turkey by the Australians and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC). Over the decades, however, it was expanded to honor the memory of all who served in the military forces of those countries. Hence, the ANZAC Day ceremonies held annually on 25 APR in Kanchanaburi were centered around the POWs who worked the Thai-Burma Railway.

By 2020, few of those POWs were able to attend due to advanced age. Following the suspension of all such gatherings during the world-wide COVID outbreak, it was seemingly decided that future annual events will be limited to a dawn service at HellFire Pass. The mid-day ceremony at the CWGC Don Rak war graves cemetery will no longer be held.

In some ways, this seems to be a reflection of the concept of who was the right and responsibility to tell the story of the TBR. Soon there will be no surviving members of that POW group. Children and grand-children are attempting to keep their memory alive, but seemingly with a scaled down remembrance ceremony.

It is somewhat sad to witness the passing of one of the largest events related to the TBR = the April Don Rak ceremony. There are still two events that remain: the 11 NOV Remembrance ceremony as organized by the Royal British Legion and the August remembrance of the Dutch POWs.

==========================

A superb example of faking your way through a vdo when you have NO IDEA what really happened. This is what passes for “history” these days with no vetting of content.

The vast majority of YOUTUBE videos found by a search are simply travelogs by tourists (see above). It is rare that any address the history of this event in any credible way.

Some are survivor accounts. I offer a few of the better ones

One of the better presentations:

Someone even had the audacity to video the presentation at the Australian HellFire Pass Centre and post it without attribution! I won’t cite that vdo.