Everyday thousands of tourists both foreign and domestic flock to take selfies on a bridge in western Thailand. If they know anything about that bridge the source is likely to be the 1957 movie: Bridge on the River Kwai. It is widely accepted that it is great theater but terrible history.

What I hope to do in this series of essays is to tell the TRUE STORY of the Thai-Burma Railway if only in summary form. That bridge is one of only a few remaining landmarks associated with that project. In reality, the 15 months it took to build that Railway are but a blink of an eye in the context of WW2 in the Pacific, but it affected the lives of hundreds of thousands.

Like all stories, it has a beginning, middle and end; each a story unto themselves. How it came to be can only be told in the larger context of the war in the South Pacific.

The PRELUDE

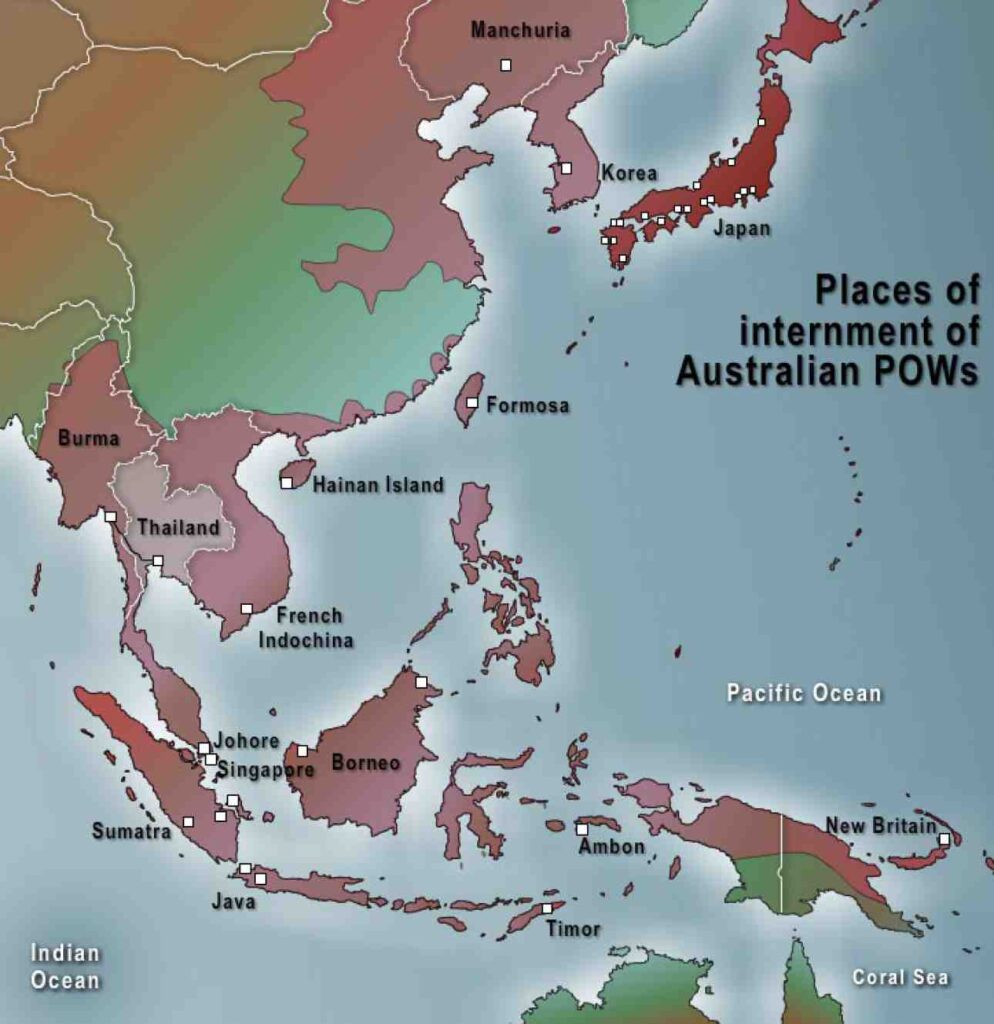

Almost simultaneously with the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese invaded Malaya through southern Thailand. Their rapid advance south caught the Commonwealth troops by surprise and with a few weeks (on Feb 15 1942) Singapore surrendered. Over 100,000 British, Australian and Indian soldiers were taken as POWs. One of Japan’s strategic goals was to seize oil reserves. Some of the largest oil fields in the world were on the islands of the Dutch East Indies (today Indonesia). These were next on the agenda. Meanwhile, the Japanese Army invaded Burma with their eye on pushing the British out of India.

With Singapore gone and the Philippines soon to follow, there was little the Allies could do stop the Japanese advance. Small Australian, British and American units were diverted to islands of the DEI, particularly Java which held the capital of Batavia (today Jakarta). On 1 Mar 42, the IJA made multiple amphibious landings on Java. The largest force of perhaps 80,000 landed at Bantam Bay in NW Java aiming at Batavia. Even supported by the Allied military units, the Dutch Colonial Army (known as the KNIL) was no match for these battle-hardened troops. Within a week, they were on the outskirts of the capital. The Dutch authorities capitulated on 8 March. Thousands more Allied troops became POWs. These included the only American troops in the area at the time.

The rapidity of the Japanese advance throughout the Pacific shocked the Allied high commands. With the US Pacific fleet crippled, the nearest Allied bases to retaliate against the Japanese were in Australia and India to include Ceylon (today Sri Lanka). The only real offensive capabilities were in the latter. Allied submarines and bombers were wreaking havoc on the ships sailing from Singapore to ferry military supplies to Burma. Tokyo needed an overland route of delivery. They dusted off a pre-WW 1 plan by the British to link Bangkok to Rangoon by rail. Both countries had extensive rail systems but they were not connected.

The MIDDLE: THAILAND

Until this time, Thailand had remained a buffer state between the British colonies to the west and French Indo-China to the east. It had never be colonized by any European nation. It, too, recognized that it could not stand up to a full Japanese invasion. So after a symbolic but futile stand on its shores, it surrendered and actually joined as a reluctant ally of Japan. Its ulterior motive was to regain territory that it had seceded to France decades before.

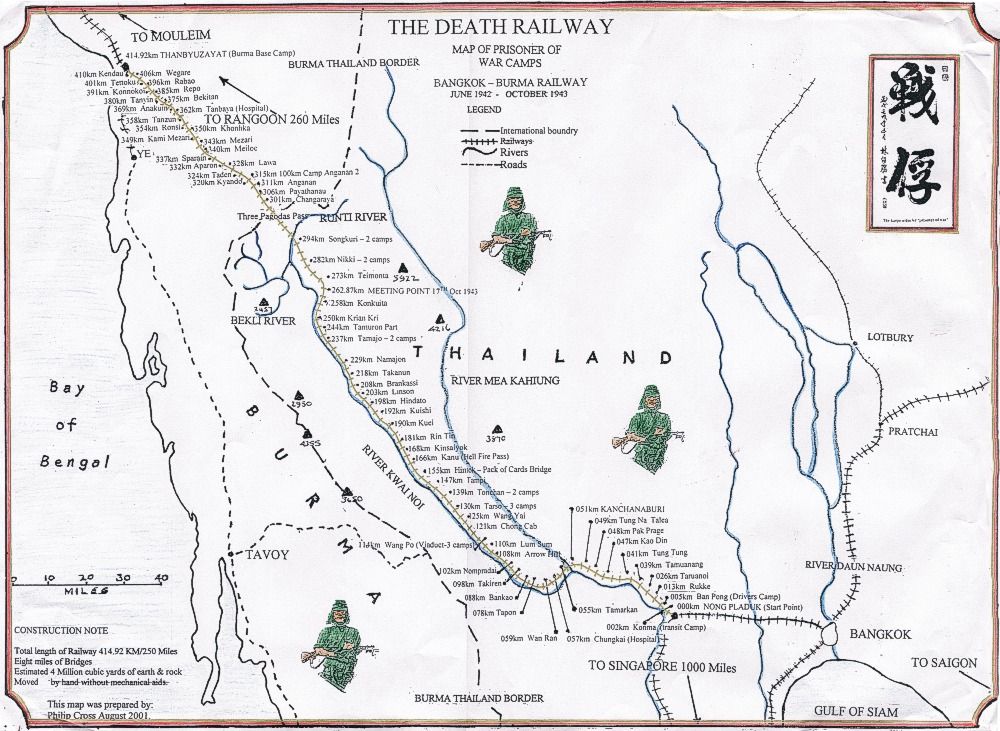

For their part the Japanese had their eye on linking Singapore, Bangkok and Rangoon by rail. So they seized control of the southern portion of the country and created what was a parallel to Vichy France by allowing the Thais to maintain governance over the bulk of the country. The missing rail link in this three-part system was a 400-kilometer stretch running to the small town of Thanbyuzayat in Burma. The British had abandoned any plans to build this link deeming it too expensive. They estimated that it would take 3-4 years. Japanese Army Railway Engineers told Tokyo that they could do it in a year! Their ace-in-the-hole were the tens of thousands of POWs who would constitute the labor force. But even the 61,000 Allied POWs who would eventually be employed were not enough. In fact, the initial plans that the Engineers had drawn up did not even include the POWs; they were an unexpected bonus. The plan was to recruit local Asian laborers by the tens of thousands. As the first of the POWs were being sent north, ‘recruitment’ of these laborers began, as well.

THE PLAN

To complete the project as rapidly as possible, work was begun at both ends. The 5th Railway Regiment was sent to Burma and work began there in June 1942. The Allied POWs sent there came primarily from those captured on Java. These were Dutch, Australians and Americans plus a few hundred British who had actually evacuated from Singapore but were captured on Sumatra. The POWs were soon joined by as many as 80,000 native Burmese and local Hilltribesmen.

The 9th Railway Regiment and the main HQ for the project was sent to BanPong Thailand. Nearby was a rail marshaling yard at NongPlaDuk where construction began officially in SEP 42. Initially, the work proceeded apace. In both counties, the terrain for 50+ kilometers was flat and unobstructed. Local Thai workers quickly laid tracks from NPD to the trading post at Kanchanaburi. By Nov 42, the HQ and logistics support operations had moved there from BanPong. Preparatory work in Burma was also easy, but a major limitation was a lack of iron rails. Other IJA Railway units were busy looting those rails as well as rolling stock from Malaya. These then had to run the gauntlet along the Andaman coast to Moulmein.

By the end of the year, however, progress slowed somewhat as major obstacles were encountered.

In Burma, construction reached the Tenasserim mountain range which forms the border with Thailand. These run north-south across the path of the Railway. Progress slowed as a series of bridges had to be built to cross the rivers that run in the valleys. To complicate matters for the laborers, this was a remote, uninhabited area of Burma with no roads or infrastructure of any kind. All supplies had to move overland from Thanbyuzayat.

At Kanchanaburi, the 9th Regiment also confronted is first major obstacle. The Mae Klong River barred their way west. It took some time to locate a place where the river bed could support a railway bridge. In late NOV 42, British POWs were moved from NPD to KAN and tasked with building first a bamboo and wooden bridge then a more permanent span. The iron for that bridge was actually looted from Java and reassembled over cement pillars built by the POWs. This is the bridge that stands today and is visited by tourists, most of whom have little or no idea of its history!

The END GAME

After 15 months of labor under the harshest of conditions, the two sectors of the Railway met at Konkoita some 40 Kms inside Thailand.

Trains immediately began carrying men and supplies to the IJA forces in Burma. But it was too little to later. The British had held the line at the border with India and Allied forces were pushing back into Burma. Returning trains were used to ferry the workers out of the jungle to ‘rest camps’ near the walled city of Kanchanaburi. Overall, camp life and conditions improved moderately; more so for the POWs than the romusha. The many maladies that had plagued these men in the jungle still continued to claim lives. Finally, the IJA established the first true hospital at Nakorn Pathom. The medications and interventions available there saved many lives. The romusha were offered no such respite.

Within weeks following the end of the war, the POWs were first evacuated to military facilities then, as rapidly as possible, began the journey home. Most were in their home country, if not home with family, by the end of the year.

Again, not so for the romusha. Not only were they deprived of adequate food shelter and medical care, no one assisted in their return home. Many remained in these camps until 1947. Some made the long walk back south; others decided to begin new lives in Thailand.

And there is the briefest of summaries of the TRUE STORY of the Thai-Burma Railway.