In Summary:

My group of intrepid investigators (primarily TS) has uncovered documents revealing that what appeared to be two findings was actually only one!

The story proceeds as described about the dreams that led to the examination of the sugar cane field exposing up to 400 sets of remains. In the end, these were separated into three groups:

1. The largest group (about 300 sets of remains) were cremated by the Bodhibhava Foundation for making merit and brought to the cemetery in Saraburi. There is worship during Qingming every year.

2. The bodies of 106 bodies were taken to the museum near the Bridge over the River Kwai. These are currently on display at that museum as shown in the vdo below. [see Section 14]

3. The bodies of 35 bodies were requested by Achaan Worawut Suwanarit and deposited at the Office of the Arts Department at Prasat Muang Sing (PMS). The Director of Arts Khun Sathaporn Kwanyuen later had these bodies buried in the ground. The reason was that the storage room where the skeleton was stored had a musty smell. At present, it is not known precisely where those bodies were buried in the park since all directly involved have since retired.

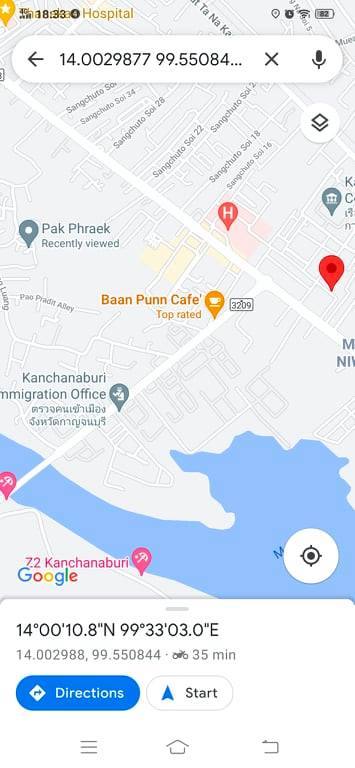

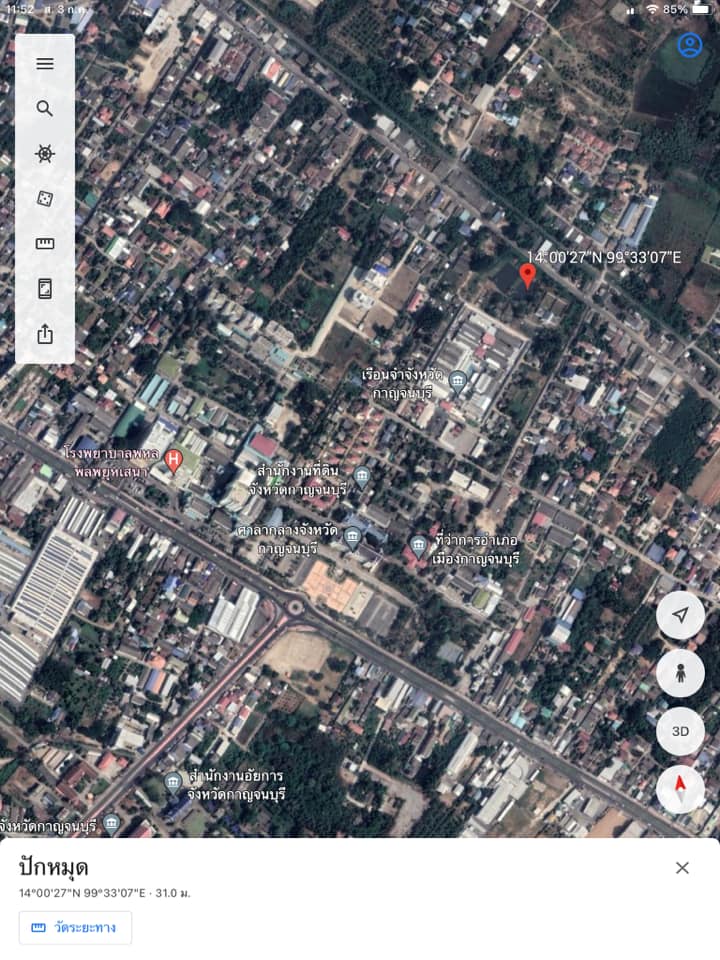

As to the field itself, it is known to have been located on the south side of the modern city very near the large hospital, Paholpolpayujasena, at either 14.0029877 N; 99.5508442 E or 14.00104N; 99.33102 E . This is thought to be near the war-era HQ of the dreaded Kempeitai Secret Police.

I have chosen to leave the earlier portion of this section unedited as it was originally written as a question about these remains.

Part 1:

Wat ThaWorn Wararam orWat Yuan Vietnamese name is Kan Taw Ter

On 1 July 2021, I visited and spoke with Khun Napparat dTetanown = manager / administrator of the Wat Yuan Cemetery.

He explained that this temple is over 200 yrs old and the current 11 rai of land (not including the cemetery) is but a small part of the prior holdings that once extended across what is now SangChuto Rd. The cemetery pre-dates WW2.

He explained the meaning of the various buildings in the cemetery: [see the Gallery below; tap the pix to expand to full size]

First the obelisk located almost central in the cemetery is the burial site of as many as 10,000 sets of remains that were found just after WW2 as SangChuto Road was being widened. The area across from the Wat Yuan Cemetery (just SE of CWGC Don Rak Cemetery) was known to be the space that many of the romusha workers were consolidated into as part of the larger Kanchanaburi POW camp.

He further related that over the years there have been at least three burial ceremonies as other road building and construction projects unearthed more remains. He noted that the chamber under that obelisk is a minimum of 7m deep. He expressed his belief that although the vast majority belonged to romusha of many Asia countries, some of the remains are of foreigners = Allied POWs. [see below]There is no evidence that the Kanchanaburi camp held any Allied citizen internees. He loosely translated the inscription on the face of the obelisk as “We are all equal; none higher, none lower than the other.”

He pointed out that to the right (SE) of the obelisk the colorful memorial is the Chinese equivalent of a spirit house for the cemetery. Off to the left, is a small Chinese-style building that serves as a chapel for annual rights performed by the family members of those buried in this cemetery. The vast majority of graves are simple Chinese graves and Thai-style chedis of ordinary people.

Also to the left of the obelisk and closer to the main road is a rather large structure with 5 chedis atop it. This is the gravesite of the WW2-era abbot.

One other grave located in front (on the same side as the inscription) is that of the Vietnamese-Thai man who contributed many of the buildings at the current temple complex. This is a simple gray granite structure that is festooned with VN-style lion statues.

Khun Napparat himself is of Chinese heritage but he noted that the area of the city behind the CWGC Cemetery has many families of Vietnamese ancestry. Indeed as we approached the temple gate we noted 2 Vietnamese restaurants. Apparently many of the first refugees arrived from Vietnam during the reign of King Rama 2 when the temple was founded and was known as Wat Yaun (Yuan is the Thai slang for Vietnam). It was re-named Wat Thaworn by King Rama 5 who granted it royal status. Today, nothing remains of the WW2-era or older buildings.

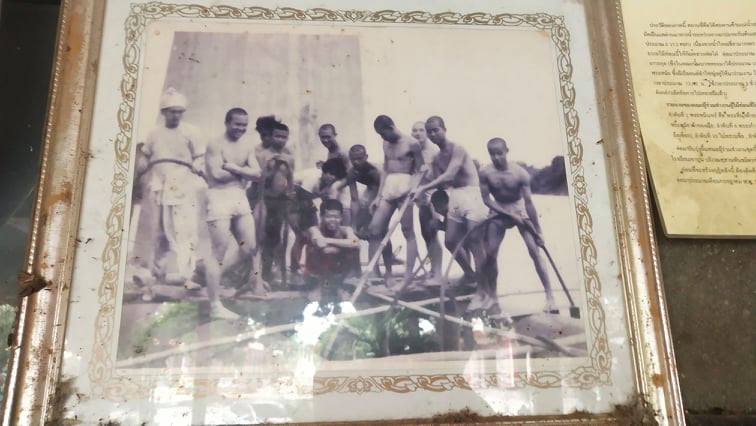

He pointed out a framed photo hanging nearby as dating back to the post-WW2-era and depicts worker building one of the current temple buildings. I inquired about the 1990 story of the unearthing of about 400 sets of remains from a sugar on the north side of the city. He denied any knowledge of that event. [see Part 2 below]

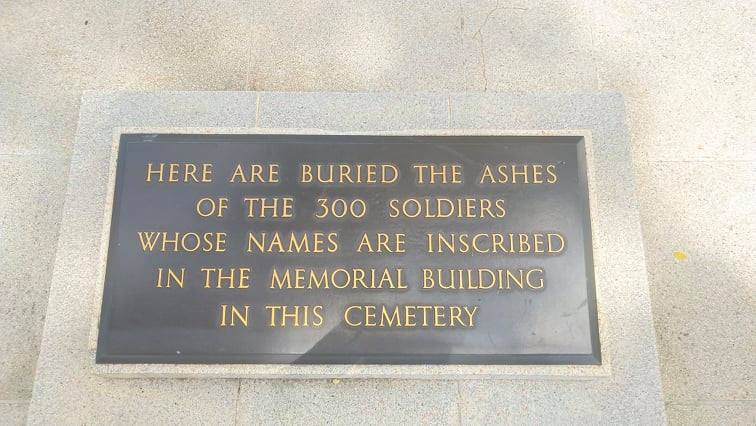

As to Khun Nattapat’s belief that Allied POW remains are included those of the Asians, this is highly unlikely. Even with the threat of punishment for doing so, Allied Officers kept quite good records of their charges and particularly of those who perished. Not every set of remains was recovered by the immediate post-war searchers (often accompanied by those who had laid the men to rest), but the names and circumstances of the deceased are known even when their remains were not recovered. There is a mass grave at the Don Rak CWGC cemetery that contains the ashes of some 300 bodies that the IJA demanded by burned not buried when they died of cholera. There is also a plaque at that site with the names of a few dozen Dutch POWs whose remains were not found. This combined with the area of the WW2 camp where the remains were found, all speaks against there being any Allied personnel included in these burials.

As to the belief by some that this monument is in some way related to IJA soldiers, that too, seems patently false. Although it is not impossible, there is no reason that any such remains would be present in this area. For most of the time of the TBR construction and afterward, Kanchanaburi was indeed an IJA HQ and supply base, but few if any IJA soldiers are known to have died there. The Japanese took great effort to honor their fallen comrades; seemingly some were repatriated to Japan after the war as well. We also know that a memorial was erected at Wat Dan Toom in BanPong dedicated to as many as 100 IJA soldiers who died. But they are thought to have died in that area not 50 Kms away in Kanchanaburi.

If anything, this memorial obelisk is a partner to the Thai-anusorn Cenotaph located near the famous Bridge. [See Section 10c]

In thanks, for the information he provided I made a contribution to the temple.

Here is an example of what can be found on the internet that just CONFUSES the story of what TRULY happened:

I want to know must know Unknown Soldier and Workers Memorial It is another monument related to World War 2 related to the construction of the Death Railway in Kanchanaburi. Many people must have been through this memorial for some time. Some people know where to go But there are some people who don’t know yet. This memorial is one of Kanchanaburi’s memorials related to World War II, especially in Kanchanaburi, there are many that are still important. (I’m trying to collect as many World War II-related monuments as I can research.)

This memorial is a memorial located at the cemetery of Wat Thavorn Wararam (Wat Yuan) used to collect the bones of soldiers and laborers who died in the construction of the Death Railway. This monument was built in 1951. The monument is a square pedestal like the Thai-anusorn Monument at the River Kwai Bridge. Wat Thavorn Wararam cleared the cemetery after being abandoned for more than 30 years. This clearing of the cemetery has found the bones of prisoners of war and laborers who were conscripted to build the Death Railway. And brought to the cemetery at this Yuan temple, more than 4,500 bodies, most of them Chinese, Indians, Malays and Indonesians. This cemetery is adjacent to the Kanchanaburi Allied War Cemetery fence. (Don Rak) has an area of about 10 rai, but because there is no message telling the history of this monument Therefore, it is not widely known.

It is another forgotten monument.

Lek Ban Tai

Part 2: A mass romusha grave in Kanchanaburi:

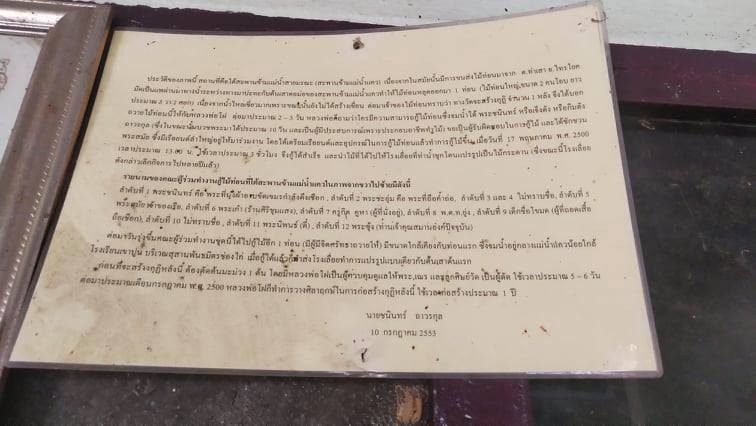

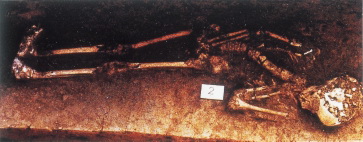

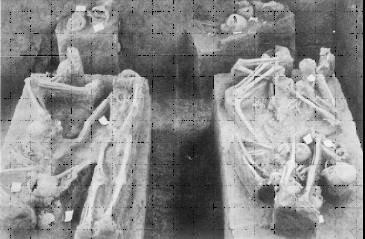

A young man was plagued by ‘bad dreams’ that seemed to lead him to a sugar cane field on the outskirts of the modern city of Kanchanaburi. He approached to owner of that newly harvested field in Oct 1990 and convinced her to have some workers dig into the earth. They soon exposed skeletal remains, dozens of them. She called on the assistance of the History and Cultural College in Nakorn Pathom and them completed the excavation of about 400 bodies. These were later determined to be ethnic Tamils. They had been almost certainly buried in 1944-45 as the Allied POWs and romusha were consolidated from up and down the TBR to the Kanchanaburi area. It is fairly well accepted that there was a romusha camp near the current main CWGC cemetery. The mass grave was perhaps a kilometer or so to the NW. [BANGKOK POST 18 NOV 1990] The elder sister of the owner (then 75yo) related that she had watched daily (in 1945) as bodies were removed from the ‘hospital’ used by Tamil (Indian) and Malayan workers from the TBR. In actuality, these were little more than death houses where the sick — many with cholera — were sent from the camp area.

In Februrary 1991, the director of the nearby Muang Singh Historical Park published a report on the excavation in the Sinlapa Wathanatham magazine of the university. The remains had been turn over to the Chinese Jin Siang Tung organization fro cremation. He also states that there were likely many more remains still undiscovered since the owners of adjacent fields would not grant permission for excavations to be carried out there. He estimates that the excavated area was no more than a half an acre. All indications were that there were women and children included in these burials. One person interviewed stated that they say some of the ‘bodies’ moving as they were being buried. This supports other claims by Allied POWs that the Japanese would order the burial of cholera patients before they were actually dead.

Much of the above text and 3 photos are derived from Kyoto-Seika Univ Professor David Boggett’s essay #25

Part 3: Controversy over WW2-era skeletal finds

This story is even more bizarre: I have an undated copy of a LONDON MAIL article – thought to be mid-1990s. It relates that a local jeweler who is linked to the recently opened JEATH #2 museum near the Bridge is purported to have on display skeletal remains that are seemingly linked to Australian POWs who worked the TBR.

I am in the midst of searching for any and all information on this topic. One part of the story is told here in Thai:

But Thai journalism is not known for hard-hitting investigative reports, so this is a fluff-piece!

Also see Section 19h for additional information on this topic.